‘RELIGION IS INTRINSIC TO HUMANITY’ – KAREN ARMSTRONG

Religion and spirituality are subjects that many intellectuals in both the East and the West broach with great caution, if it all. Not Karen Armstrong. The British scholar has a genuine interest and great passion for studying, writing and talking about all things that concern man’s plight to discover the ultimate.

Religion and spirituality are subjects that many intellectuals in both the East and the West broach with great caution, if it all. Not Karen Armstrong. The British scholar has a genuine interest and great passion for studying, writing and talking about all things that concern man’s plight to discover the ultimate.

Invited recently to Pakistan for a lecture tour to celebrate the golden jubilee of Prince Karim Aga Khan’s ascension to the Ismaili imamate, Ms Armstrong took a few minutes to speak to Dawn amid a hectic schedule of media interviews and lectures. Here are excerpts from the conversation.

– Q : You’ve described yourself as a ‘freelance monotheist.’ Would you care to elaborate ?

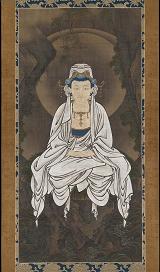

A: I once said that in a glib way and it’s dogged my footsteps ever after. What I meant at the time was that I draw nourishment from all three religions of Abraham — Judaism, Christianity and Islam. I can’t see any one of them as superior to any of the others. But since then I’ve extended my interest and appreciation to faiths that are not centred on God, to Buddhism for example. I’ve written about the Buddha. In my book The Great Transformation I’ve included the oriental religions, which aren’t theistic in our sense.

A: I once said that in a glib way and it’s dogged my footsteps ever after. What I meant at the time was that I draw nourishment from all three religions of Abraham — Judaism, Christianity and Islam. I can’t see any one of them as superior to any of the others. But since then I’ve extended my interest and appreciation to faiths that are not centred on God, to Buddhism for example. I’ve written about the Buddha. In my book The Great Transformation I’ve included the oriental religions, which aren’t theistic in our sense.

– Q: But are there traces of monotheism in Buddhism?

A: No, because the Buddhists don’t like the idea of God to express the ultimate. They don’t have an idea of a creator. For them, they say that that’s too limiting to apply to God because we often talk about God in too personalized a way. Muslims do it less actually than Jews or Christians. The Quran’s is a much more transcendent God, less anthropomorphic than the God of the Bible, or the incarnate God in Christianity. Buddhists feel that to speak about God is too limiting to apply to Nirvana, which goes beyond all human concepts.

– Q: You’ve received some flak for your biography of the Holy Prophet (PBUH). Some critics have called it revisionist and inaccurate. How would you respond to that?

A: I don’t think it’s particularly revisionist. I think it’s in line with the latest scholarship. I don’t know who these critics are. I never read reviews. What I wanted to do was show the magnitude of the Prophet’s (PBUH) life.

– Q: All three Abrahamic faiths, as well as Hinduism and Buddhism, are awaiting a saviour who will establish peace and justice on earth. Is everyone waiting for the same person ?

A: I think this is symbolic. Not all Muslims are waiting for a saviour. I don’t think this is particularly strong in the Sunni tradition. Christians have had their saviour in Jesus. The Messianic idea in Judaism is really a very minor part of it. So I think the idea of a saviour is more of a symbolic way of looking forward to a better time, of thinking there must be a way out of this present impasse. But apocalyptic theories are a bit dangerous because they can often be quite vengeful about people who don’t belong to one’s own tradition. That seems too antagonistic to religion.

“I think that the desire to live in touch with transcendence is a human characteristic.”

– Q: Are people by nature essentially religious?

A: Yes. I think that the desire to live in touch with transcendence is a human characteristic. As soon as human beings came out of the caves, we started creating religions and works of art to express that life has transcendence. We’re also meaning-seeking creatures. We need meaning in our lives. If we don’t have meaning in our lives we fall very easily in despair. We’re unique in the animals in this respect.

You don’t see cats and dogs agonizing about their feline and canine condition or worrying about the plight of dogs and cats in other parts of the world or in the afterlife. But human beings, we do ask these questions; ‘why does this happen?’ A dog, when it gets ill, just goes with it. You don’t see it saying ‘why me’ or ‘what’s happened.’ It is a complete acceptance. We have the capacity to look back and look forward. We have to live with our own mortality, which is a disturbing thing for us.

It’s also a characteristic of the human mind that we have ideas and experiences that go beyond what we can grasp or understand. The world has always been mysterious to us, and it continues to be so even with the advance of modern science. For all these reasons religion is intrinsic to humanity. But that doesn’t mean that any particular religious ideas or symbols are intrinsic to humanity. These often change over time.

– Q: So is atheism not in line with human nature?

A: Modern atheism is a modern experiment, a modern condition. The secularism of Western Europe – not of America, which is a very religious country – is new, I think, in the history of humanity. I think that’s come about largely as a result of our modernity because since about the 17th century Christians have written about God in such a rationalistic way in the West that they’ve made God incredible.

A: Modern atheism is a modern experiment, a modern condition. The secularism of Western Europe – not of America, which is a very religious country – is new, I think, in the history of humanity. I think that’s come about largely as a result of our modernity because since about the 17th century Christians have written about God in such a rationalistic way in the West that they’ve made God incredible.

– Q: You’ve said that fundamentalism is a product of the modern age. Does its antidote lie within religion or in moving further away from it?

A: Fundamentalism is a complex phenomenon. It’s not a revolt against religion so much as it’s a revolt against secularism in every region where a modern secular-style government has established itself. A religious counter-culture develops alongside it aiming to bring God and all religion back to centre stage. You have it in Buddhism, Hinduism, Confucianism, as well as all three of the monotheistic traditions.

And it’s a product of the modern period, these innovative, unorthodox theologies that are against the mainstream. Often, in their anxiety to protect religion, which they perceive to be in danger, fundamentalists usually distort the tradition that they’re trying to protect, emphasizing its more belligerent aspects and down-playing those that speak of compassion and respect for others.

Attacking fundamentalism is counter-productive. History shows that when you attack these movements, they become more extreme. That means attacking them in the media as well as with guns. Membership of al-Qaeda, for example, has grown enormously since the invasion of Iraq. It was an absolute gift to al-Qaeda. People are convinced that modern secular society wants to wipe out religion when they see Muslims, for example, under attack; they say ‘we were right. This is what the modern world wants to do.’

You have to listen to the fears and anxieties that underlie fundamentalism. Be careful not to align fundamentalism with terrorism inextricably. Only a tiny, tiny proportion of fundamentalists take part in acts of terror and violence. Most of this terrorism is far more political rather than religiously motivated. Here in Pakistan it is almost tribally motivated.

The answer to this problem is to redress some of these political grievances, to sort out these outstanding political problems such as the Arab-Israeli conflict and Kashmir, which have been allowed to fester, become symbolic and have introduced a kind of malaise.

Also, (there’s) the western habit of promoting really awful rulers to get cheap oil or to secure their strategic positions in an oil-rich region – e.g. the Shah of Iran, Saddam Hussain etc. This creates a malaise in society. (Under) dictatorial regimes, people can’t express their discontent anywhere except the mosque, which makes the whole of religion problematic.

There’s an imbalance of power in the world – too much power residing with too few people. Whether we like it or not, we are in a global world. What happens today in Afghanistan or Pakistan will have repercussions in Washington and London tomorrow in all kinds of ways.

Par Qasim A. Moini

Source: www.Dawn.com