– POUR VOIR LA VIDEO, CLIQUEZ ICI : ENTRETIEN AVEC THICH NHAT HANH SUR LE BOUDDHISME ENGAGE

BURMA’S MONKS: ALREADY A SUCCESS [[Traduit de l’Anglais par Hélène LE, pour www.buddhachannel.tv]]

– Moines de Birmanie: « Déjà un succès »

Friday, Oct. 12, 2007 By DAVID VAN BIEMA/NEW YORK CITY

– Vendredi 12 octobre 2007 par DAVID VAN BIEMA/NEW YORK CITY

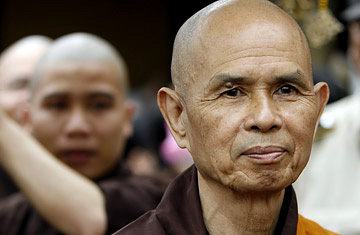

The monk sat cross-legged in the Manhattan hotel room in augbergine robes on an aubergine prayer mat, a thermos of tea, his reading glasses and a book, Mindfulness in the Marketplace, arranged neatly by his side. Thich Nhat Hanh took time out from a U.S. tour to speak briefly with TIME about the monastic uprising in Burma. (See video Video- David Van Biema Interviews Thich Nhat Hanh).

– Le moine est assis en tailleur dans la chambre d’hôtel de Manhattan dans sa robe aubergine sur un matelas de prière aubergine, un thermos de thé, ses lunettes de lecture et un livre, Mindfulness in the Marketplace, bien posé sur le côté. Thich Nhât Hanh consacre du temps pris sur sa tournée des U.S.A, pour parler brièvement au TIME du soulèvement monastique en Birmanie. (Voir vidéo-Interviews de Thich Nhât Hanh par David Van Biema)

Nhat Hanh has a long history as one of Buddhism’s truly international spokespeople. [« Thich » is a name adopted by all Vietnamese monks and nuns upon ordination.] He first came to global attention in the early 1960s, when he led fellow monks in his native Vietnam to oppose the prosecution of the war there by either side — a position that eventually led to the deaths of several of his followers and his own exile. He continued his opposition from the United States, where his counsel was influential in convincing the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to announce his own opposition to the conflict. King subsequently nominated Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize. He continued speaking and writing (in a variety of languages — he is a polyglot), working out a theory of « engaged Buddhism, » exploring the commonalities between his philosophy and other world faiths, attaining a popularity (and book sales) in the U.S. second only to that of the Dalai Lama, and lending his opposition to a series of world conflicts, including America’s involvement in Iraq. He now lives in a monastic community he founded in France.

– Nhât Hanh a une longue histoire en tant que véritable porte-parole international du Bouddhisme. [« Thich » est un nom adopté par tous les moines et nonnes vietnamiens ordonnés.]Il est apparu à l’attention général pour la première fois au début des années 1960, lorsqu’il a dirigé des moines dans son Vietnam natif en opposant une condamnation de la guerre à tous les partis – une position qui a finalement conduit à la mort de plusieurs de ses disciples et à son propre exil. Il a continué sa résistance des Etats-Unis, où ses conseils ont convaincu le Rév. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. d’annoncer sa propre opposition au conflit. King a ensuite nommé Hanh pour le Prix Nobel de la Paix. Il a continué à parler et écrire (dans plusieurs langues-il est polyglotte), travaillant une théorie du « Bouddhisme engagé », explorant les points communs entre sa philosophie et d’autres fois du monde, atteignant une popularité (et des ventes de bouquins) aux Etats-Unis, en deuxième place après celle du Dalaï Lama, et appliquant son opposition à une série de conflits mondiaux, incluant l’implication de l’Amérique en Irak. Il vit actuellement au sein d’une communauté monastique qu’il a fondé en France.

Buddhism has three major branches: Theravada, historically the simplest, which is now practiced primarily in South Asia and is the faith of the Burmese monks; Mahayana, of which Hanh’s own Zen discipline is part; and the Dalai Lama’s Tibetan branch, which is labeled Vajrayana. In conversation, however, Hanh stressed the unity of the three and their solidarity with the embattled Burmese. « They also practice mindfulness and concentration inside like us, » he said.

– Le Bouddhisme a trois branches majeures: le Theravada, le plus simple historiquement parlant, qui est maintenant pratiqué principalement en Asie du Sud et qui est la foi des moines birmans; Mahayana, de laquelle la discipline Zen de Hanh fait partie; et la branche tibétaine du Dalaï Lama, appelée Vajrayana. Toutefois, au fil de la conversation Hanh insiste sur l’unité des trois et leur solidarité avec les Birmans opprimés. « Ils pratiquent aussi la Pleine Conscience et la concentration intérieure comme nous » précise t-il.

He said the Burmese monks had « done their job. It is already a success because if monks are imprisoned or have died, they have offered their spiritual leadership. And it is up to the people in Burma and the world to continue. » Pressed on the question of martyrdom, he replied: « We nourish the awareness that monks are being persecuted and continue to suffer in order to support the people in Burma for the sake of democracy. »

– Il a affirme que les moines birmans ont « fait leur travail. C’est déjà un succès car si les moines ont été emprisonnés ou sont morts, ils ont offert leur direction spirituelle. Et c’est maintenant au peuple de Birmanie et au monde de continuer ». Questionné sur le martyr, il répond: « nous nourrissons la conscience que les moines sont persécutés et qu’ils continuent de souffrir afin de soutenir le peuple en Birmanie pour le salut de la démocratie. »

Perhaps the most striking gesture made by his Burmese brethren before they were attacked was the symbolic act of turning their begging bowls upside down. In a Western culture where almsgiving happens in the confines of a church or synagogue, this may have seemed odd. But Nhat Hanh pointed out that it was a powerful statement of denial to the regime leaders. « In Buddhist culture, » he explained, « offering food to the monk symbolizes the action of goodness, and if you have no opportunity to support the practice of spirituality then you are somehow left in the realm of darkness. » Their supreme act of condemnation: giving the regime no chance to do good. The importance of monks in Burma was also suggested, in a grisly way, by reports that hundreds of Burmese soldiers had been arrested for refusing to shoot at them.

– Le geste le plus frappant accompli par ses frères birmans avant d’être attaqués, a sans doute été l’acte symbolique de retourner leurs bols de mendiant vers le sol. Dans la culture occidentale où l’aumône se déroule aux confins d’une église ou d’une synagogue, cela a pu paraître étrange. « Dans la culture bouddhiste » explique t-il, « offrir de la nourriture aux moines symbolise une action généreuse, et si vous n’avez pas l’opportunité de soutenir la pratique de la spiritualité, vous êtes en quelque sorte abandonné dans le royaume de l’obscurité ». Leur acte suprême de condamnation: ne pas donner au régime une chance de faire le bien. L’importance des moines en Birmanie a aussi été suggérée, d’une façon macabre, par des comptes-rendus de centaines de soldats birmans arrêtés pour avoir refusé de leur tirer dessus.

In the U.S., the connection between Buddhism and social action is not readily understood. Many Americans perceive Buddhism as a philosophy that regards this world as transitory and unimportant; in this country, the most widely disseminated kind of Buddhism is a stripped-down version of Theravada practice with a strong emphasis on ritual supplemented by meditations on meta, or loving-kindness. Said Nhat Hanh: « Meditation is to get insight, to get understanding and compassion, and when you have them, you are compelled to act. The Buddha, after enlightenment, went out to help people. Meditation is not to avoid society; it is to look deep to have the kind of insight you need to take action. To think that it is just to sit down and enjoy the calm and peace, is wrong. »

– Aux Etats-Unis, le lien entre le Bouddhisme et l’action sociale n’est pas encore compris. Beaucoup d’Américains perçoivent le Bouddhisme comme une philosophie qui concerne ce monde, transitoire et sans importance; dans ce pays, la forme la plus répandue du Bouddhisme est une forme simplifiée de la pratique du Theravada avec une insistance forte sur un rituel soutenu par des méditations du Meta, ou la bonté aimante. Nhât Hanh dit encore: « La méditation, c’est de parvenir à la pénétration, la compréhension et la compassion, et lorsque vous y parvenez, vous devez agir. Le Bouddha, après l’illumination, est sorti afin d’aider le peuple. La méditation ne signifie pas éviter la société; elle signifie regarder au plus profond de soi afin de trouver une forme de pénétration nécessaire à l’action. Penser qu’elle ne consiste qu’à s’asseoir et profiter du calme et de la paix, est une erreur. »

After a brisk interview about Burma, Nhat Hanh gave some sense of the topics that were most on his mind that afternoon: he talked first about global warming and then about eating low on the food chain. He told a Buddhist story of a couple who were forced to cross a desert with their young son and, running out of food, killed and ate the child, whose diminishing corpse they carried with them, constantly apologizing to it. « After the Buddha told that story, he asked the monks, ‘Do you think the couple enjoyed eating the flesh of their own son?' » Nhat Hanh recounted. « The monks said ‘no, impossible.’ The Buddha said, let us eat in such a way that will retain compassion in our heart. Otherwise we will be eating the flesh of our son and grandson. » It was a stark and stern reminder of the steel beneath the flowing robe, gentle smile and peaceful demeanor.

– Après un rapide entretien sur la Birmanie, Nhât Hanh a abordé les sujets qui le préoccupaient cet après-midi: le réchauffement climatique, puis d’une attitude raisonnable au sein de la chaîne alimentaire. Il a raconté l’histoire bouddhiste d’un couple forcé de traverser un désert avec leur jeune fils et qui, manquant de nourriture, tua puis mangea son enfant. Il ne cessait de demander pardon au cadavre rapetissant emporté avec eux « Après que le Bouddha eut raconté cette histoire, il demanda aux moines, « Pensez vous que le couple a apprécié manger la chair de son propre fils? » continue Nhât Hanh. « Les moines répondirent « non, impossible ». Le Bouddha dit, laissez nous manger de telle sorte que la compassion soit retenue dans notre coeur. Autrement, nous mangerons la chair de notre fils et de notre petit-fils ». Ce fut là, un rappel sévère et brutal de l’acier sous les robes flottantes, le sourire bienveillant et l’attitude pacifique.

Source : Time