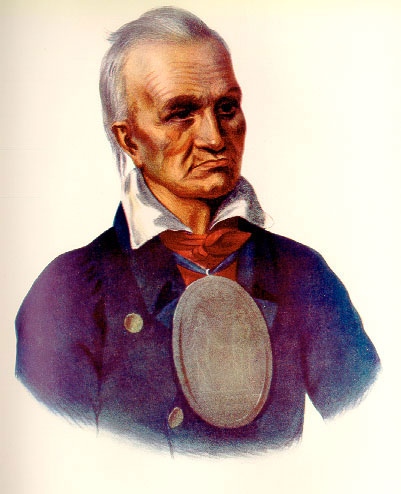

Red Jacket

(Segoyewatha or Sagu-ya-what-hath – Keeper-Awake)

(c. 1750-1830)

Seneca orator and political leader, Red Jacket was called Otetiani, usually translated as “Always Ready.”

Born into the Wolf clan in a Seneca village near present-day Geneva, New York, he came of age during the most stressful era of his people’s history. The American War of Independence deeply split the Six Nations of the Iroquois, of which the Senecas were both the westernmost and the most populous member. Ultimately, however, most of the Iroquois nationsincluding nearly all Seneca factionssided with the British. That choice was disastrous. As fighting ended in the early 1780s, several thousand refugees were living near British Niagara, their villages destroyed by U.S. forces in 1779. When the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783, they had only begun to reoccupy homes that European diplomats had placed within the victorious state of New York.

During the war, Red Jacket had been a messenger for British officers and, so the story goes, received his namesake coat as a reward. On the whole, however, his military career was undistinguished, if not, as the political opponents who called him Cow Killer alleged, cowardly. His talents lay instead in diplomacy, and particularly in oratory, a skill long prized in Iroquois political culture. Sometime in the 1780s he assumed the ceremonial role of council orator, and with it the name Segoyewatha, traditionally translated as “He Keeps Them Awake,” but more accurately rendered “He Makes Them Look for It in Vain.”

Red Jacket’s oratory marked nearly every major treaty council between whites and Senecas from the 1780s to the 1820s. Iroquois traditions of political consensus required him to pose as spokesman for all Senecas. But usually he articulated a diplomatic middle course between two competing factions. On one side were the followers of his fellow Seneca Cornplanter, who pursued accommodation with U.S. and state authorities; on the other were the supporters of the Mohawk Joseph Brant, who continued his wartime alliance with the British and in 1785 led nearly half of the Six Nations population to new homes on the Grand River in present-day Ontario. Between these extremes, Red Jacket’s positions were consistent: the Iroquois Confederacy should remain neutral in disputes between the United States and British Canada; broker an honest peace between the new republic and the Shawnees, Miamis, and other western Indians with whom it remained at war; resist Christian proselytization; andabove allmaintain a land base within the boundaries claimed by the state of New York.

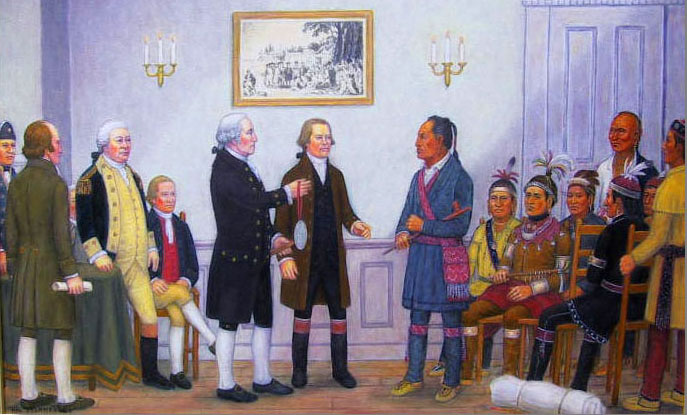

His success was mixed. Red Jacket was at his best with stirring speeches that inspired his followers and rebucked Euro-Americans. In 1792, for instance, when President Washington summoned him to Philadelphia in hopes that the Senecas would bring the western Indians to peace, the orator minced no words. “The President has assured us that he is not the cause of the hostilities,” he said. “Brother, we wish you to point out to us . . . what you think is the real cause.” Similarly blunt was the most famous speech attributed to Red Jacket, an 1805 response to a Christian missionary. “The Great Spirit . . . has made a great difference between his white and red children,” he declared. “We do not wish to destroy your religion or take it from you. We only want to enjoy our own.”

Oratory alone, however, could not solve the Senecas’ problems. Moreover, a long tradition of factionalized, decentralized politics ensured that no single policy could be pursued consistently and that federal, state, or private interests could always find leaders who could be coerced or bribed into surrendering Iroquois lands. By these means, treaties at Fort Stanwix in 1784, Big Tree in 1797, and Buffalo Creek in 1826 created a paper trail depriving Senecas of all but a tiny fraction of western New York. Despite his vigorous opposition during and after treaty councils, Red Jacket signed the Big Tree and Buffalo Creek documents and occasionally accepted cash from white negotiators. Perhaps, as some alleged, he sold out. Or perhaps his resistance was outweighed by his commitment to Iroquois unity and his ambition to remain at the center of power.

Whatever the case, Iroquois politics remained anything but unified. In 1801, for example, Cornplanter’s half brother, the prophet Handsome Lake, accused Red Jacket of witchcraft and nearly had him executed. Four years later, Red Jacket’s quarrel with Brant climaxed during a dispute between Canadian officials and the Grand River Iroquois over the terms of their royal land grant. While Brant’s ally, the adopted Mohawk John Norton, sought support at Whitehall, Red Jacket helped convene a rump council that repudiated Norton’s transatlantic mission and briefly deposed Brant. After the latter’s death in 1807, Red Jacket’s principal factional foes were Seneca Christians. In 1824, his “Pagan” faction used an obscure state law to win the temporary expulsion of the missionary Thompson S. Harris and to close his school on the Buffalo Creek Reservation. Three years later, the Christian faction retaliated with a written document ousting Red Jacket as orator.

By the time a subsequent council reinstated him, Red jacket had become a celebrity among white audiences captivated by stereotypes of the “Vanishing Indian.” Charles Bird King, George Catlin, and others painted portraits of the man people were calling “the last of the Senecas,” yet his final decade was hardly happy. To the devastating results of the Buffalo Creek Treaty and his battles with political enemies were added the indignity of public appearances that resembled carnival sideshows, the humiliation of his wife’s conversion to Christianity, the pain of ill health, and, probably, the demon of alcoholism. His last trip eastward, in 1829, took him to Washington, D.C., where he met the newly inaugurated president, Andrew Jackson. While en route home Red Jacket appeared before an Albany, New York, audience made up largely of Jacksonian state legislators. In a rambling speech that inspired most of the assembled worthies to walk out, he compared Old Hickory unfavorably with the nation’s first president.

Home at Buffalo Creek, knowing the end was near, Red Jacket made a round of farewell visits. “Let my funeral be according to the customs of our nation,” he reportedly said. “Be sure that my grave be not made by a white man; let them not pursue me there!” When death came on January 20, 1830, however, the Christian faction appropriated his corpse, prepared it for a Protestant service, and interred it in a grave indeed dug by whites. These acts were bitter symbolic blows to the causes Red Jacket had stood for. Yet, paradoxically, his enemies’ need to appropriate him in death as they could not in life affirms the magnitude of his legacy.

Seneca Chief Red Jacket: Address to the Iroquois Nation

“We do not quarrel about religion”

Friend and Brother:

It was the will of the Great Spirit that we should meet together this day. He orders all things and has given us a fine day for our council. He has taken his garment from before the sun, and caused it to shine with brightness upon us. Our eyes are opened, that we see clearly; our ears are unstopped, that we have been able to hear distinctly the words you have spoken. For all these favors we thank the Great Spirit; and him only.

Brother:

this council fire was kindled by you. It was at your request that we came together at this time. We have listened with attention to what you have said. You requested us to speak our minds freely. This gives us great joy; for we now consider that we stand upright before you, and can speak what we think. All have heard your voice, and all speak to you now as one man. Our minds are agreed.

Brother:

you say you want an answer to your talk before you leave this place. It is right you should have one, as you are a great distance from home, and we do not wish to detain you. But we will first look back a little, and tell you what our fathers have told us, and what we have heard from the white people.*

Brother:

listen to what we say.

There was a time when our forefathers owned this great island. Their seats extended from the rising to the setting of the sun. The Great Spirit had made it for the use of the Indians. He had created the buffalo, the deer, and other animals for food. He’d made the bear and the beaver, and their skins served us for clothing. He had scattered them over the country, and had taught us how to take them. He had caused the earth to produce corn for bread. All this He had done for his red children, because He loved them. If we had any disputes about our hunting grounds, they were generally settled without the shedding of much blood.

But an evil day came upon us. Your forefathers crossed the great waters and landed on this island. Their numbers were small. They found friends and not enemies. They told us they had fled from their own country for fear of wicked men, and had come here to enjoy their religion. *They asked for a small seat.* We took pity on them, granted their request, and they sat down amongst us. We gave them corn and meat; they gave us poison in return.

The white people had now found our country. Tidings were carried back, and more came amongst us. Yet we did not fear them. We took them to be friends. They called us brothers. We believed them, and gave them a large seat. At length their numbers had greatly increased. They wanted more land; they wanted our country. Our eyes were opened, and our minds became uneasy. Wars took place. Indians were hired to fight against Indians, and many of our people were destroyed. They also brought strong liquors among us. It was strong and powerful and has slain thousands.

Brother:

our seats were once large, and yours very small. You have now become a great people, and we have scarcely a place left to spread our blankets. You have got our country, but you are not satisfied; you want to force your religion upon us.

Brother:

continue to listen. You say that you are sent to instruct us how to worship the Great Spirit agreeably to His mind. And if we do not take hold of the religion which you white people teach, we shall be unhappy hereafter. You say that you are right, and we are lost. How do you know this to be true? We understand that your religion is written in a book. If it was intended for us as well as for you, why has not the Great Spirit given it to us, and not only to us, but why did He not give to our forefathers knowledge of that book, with the means of understanding it rightly? We only know what you tell us about it. How shall we know when to believe, being so often deceived by the white man?

Brother:

you say there is but one way to worship and serve the Great Spirit. If there is but one religion, why do you white people differ so much about it? Why not all agreed, as you can all read the book?

Brother:

we do not understand these things. We are told that your religion was given to your forefathers and has been handed down from father to son. We also have a religion, which was given to our forefathers, and has been handed down to us, their children. We worship that way. It teaches us to be thankful for all the favors we receive; to love each other, and to be united. We never quarrel about religion.

Brother:

the Great Spirit has made us all, but He has made a great difference between his white and red children. He has given us a different complexion and different customs. To you He has given the arts. To these He has not opened our eyes. We know these things to be true.

*Since He has made so great a difference between us in other things,* why may we not conclude that He has given us a different religion *according to our understanding?*

The Great Spirit does right. He knows what is best for his children; we are satisfied.

Brother:

we do not wish to destroy your religion, or to take it from you.

We only want to enjoy our own.

Brother:

you say you have not come to get our land or our money, but to enlighten our minds. I will now tell you that I have been at your meetings, and saw you collecting money from the meeting. I cannot tell what this money was intended for, but suppose it was for your minister, and if we should conform to your way of thinking, perhaps you may want some from us.

Brother:

we are told that you have been preaching to the white people in this place. These people are our neighbors. We are acquainted with them. We will wait a little while, and see what effect your preaching has upon them. If we find it does them good, and makes them honest, and less disposed to cheat Indians, we will then consider again what you have said.

Brother: you have now heard our answer to your talk, and this is all we have to say at present. As we are going to part, we will come and take you by the hand, and hope the Great Spirit will protect you on your journey, and return you safe to your friends.

delivered 1805, Buffalo Grove, New York