THE SILK ROAD

Introduction

The region separating China from Europe and Western Asia is not the most hospitable in the world. Much of it is taken up by the Taklimakan desert, one of the most hostile environments on our planet. There is very little vegetation, and almost no rainfall; sandstorms are very common, and have claimed the lives of countless people. The locals have a very great respect for this `Land of Death’; few travellers in the past have had anything good to say about it. It covers a vast area, through which few roads pass; caravans throughout history have skirted its edges, from one isolated oasis to the next. The climate is harsh; in the summer the daytime temperatures are in the 40’s, with temperatures greater than 50 degrees Celsius measured not infrequently in the sub-sealevel basin of Turfan. In winter the temperatures dip below minus 20 degrees. Temperatures soar in the sun, but drop very rapidly at dusk. Sand storms here are very common, and particularly dangerous due to the strength of the winds and the nature of the surface. Unlike the Gobi desert, where there there are a relatively large number of oases, and water can be found not too far below the surface, the Taklimakan has much sparser resources.

The land surrounding the Taklimakan is equally hostile. To the northeast lies the Gobi desert, almost as harsh in climate as the Taklimakan itself; on the remaining three sides lie some of the highest mountains in the world. To the South are the Himalaya, Karakorum and Kunlun ranges, which provide an effective barrier separating Central Asia from the Indian sub-continent. Only a few icy passes cross these ranges, and they are some of the most difficult in the world; they are mostly over 5000 metres in altitude, and are dangerously narrow, with precipitous drops into deep ravines. To the north and west lie the Tianshan and Pamir ranges; though greener and less high, the passes crossing these have still provided more than enough problems for the travellers of the past. Approaching the area from the east, the least difficult entry is along the `Gansu Corridor’, a relatively fertile strip running along the base of the Qilian mountains, separating the great Mongolian plateau and the Gobi from the Tibetan High Plateau. Coming from the west or south, the only way in is over the passes.

The Early History of The Region

On the eastern and western sides of the continent, the civilisations of China and the West developed. The western end of the trade route appears to have developed earlier than the eastern end, principally because of the development of the the empires in the west, and the easier terrain of Persia and Syria. The Iranian empire of Persia was in control of a large area of the Middle East, extending as far as the Indian Kingdoms to the east. Trade between these two neighbours was already starting to influence the cultures of these regions.

This region was taken over by Alexander the Great of Macedon, who finally conquered the Iranian empire, and colonised the area in about 330 B.C., superimposing the culture of the Greeks. Although he only ruled the area until 325 B.C., the effect of the Greek invasion was quite considerable. The Greek language was brought to the area, and Greek mythology was introduced. The aesthetics of Greek sculpture were merged with the ideas developed from the Indian kingdoms, and a separate local school of art emerged. By the third century B.C., the area had already become a crossroads of Asia, where Persian, Indian and Greek ideas met. It is believed that the residents of the Hunza valley in the Karakorum are the direct descendents of the army of Alexander; this valley is now followed by the Karakorum Highway, on its way from Pakistan over to Kashgar, and indicates how close to the Taklimakan Alexander may have got.

This `crossroads’ region, covering the area to the south of the Hindu Kush and Karakorum ranges, now Pakistan and Afghanistan, was overrun by a number of different peoples. After the Greeks, the tribes from Palmyra, in Syria, and then Parthia, to the east of the Mediterranean, took over the region. These peoples were less sophisticated than the Greeks, and adopted the Greek language and coin system in this region, introducing their own influences in the fields of sculpture and art.

Close on the heels of the Parthians came the Yuezhi people from the Northern borders of the Taklimakan. They had been driven from their traditional homeland by the Xiongnu tribe (who later became the Huns and transfered their attentions towards Europe), and settled in Northern India. Their descendents became the Kushan people, and in the first century A.D. they moved into this crossroads area, bringing their adopted Buddhist religion with them. Like the other tribes before them, they adopted much of the Greek system that existed in the region. The product of this marriage of cultures was the Gandhara culture, based in what is now the Peshawar region of northwest Pakistan. This fused Greek and Buddhist art into a unique form, many of the sculptures of Buddhist deities bearing strong resemblances to the Greek mythological figure Heracles. The Kushan people were the first to show Buddha in human form, as before this time artists had preferred symbols such as the footprint, stupa or tree of enlightenment, either out of a sense of sacrilege or simply to avoid persecution.

The eastern end of the route developed rather more slowly. In China, the Warring States period was brought to an end by the Qin state, which unified China to form the Qin Dynasty, under Qin Shi Huangdi. The harsh reforms introduced to bring the individual states together seem brutal now, but the unification of the language, and standardisation of the system, had long lasting effects. The capital was set up in Changan, which rapidly developed into a large city, now Xian.

The Xiongnu tribe had been periodically invading the northern borders during the Warring States period with increasing frequency. The northern-most states had been trying to counteract this by building defensive walls to hinder the invaders, and warn of their approach. Under the Qin Dynasty, in an attempt to subdue the Xiongnu, a campaign to join these sections of wall was initiated, and the `Great Wall’ was born. When the Qin collapsed in 206 B.C., after only 15 years, the unity of China was preserved by the Western Han Dynasty, which continued to construct the Wall.

During one of their campaigns against the Xiongnu, in the reign of Emperor Wudi, the Han learnt from some of their prisoners that the Yuezhi had been driven further to the west. It was decided to try to link up with these peoples in order to form an alliance against the Xiongnu. The first intelligence operation in this direction was in 138 B.C. under the leadership of Zhang Qian, brought back much of interest to the court, with information about hitherto unknown states to the west, and about a new, larger breed of horse that could be used to equip the Han cavalry. The trip was certainly eventful, as the Xiongnu captured them, and kept them hostage for ten years; after escaping and continuing the journey, Zhang Qian eventually found the Yuezhi in Northern India. Unfortunately for the Han, they had lost any interest in forming an alliance against the Xiongnu. On the return journey, Zhang Qian and his delegation were again captured, and it was not until 125 B.C. that they arrived back in Changan. The emperor was much interested by what they found, however, and more expeditions were sent out towards the West over the following years. After a few failures, a large expedition managed to obtain some of the so-called `heavenly horses’, which helped transform the Han cavalry. These horses have been immortalised in the art of the period, one of the best examples being the small bronze `flying horse’ found at Wuwei in the Gansu Corridor, now used as the emblem of the China International Travel Service. Spurred on by their discoveries, the Han missions pushed further westwards, and may have got as far as Persia. They brought back many objects from these regions, in particular some of the religious artwork from the Gandharan culture, and other objects of beauty for the emperor. By this process, the route to the west was opened up. Zhang Qian is still seen by many to be the father of the Silk Road.

In the west, the Greek empire was taken over by the Roman empire. Even at this stage, before the time of Zhang Qian, small quantities of Chinese goods, including silk, were reaching the west. This is likely to have arrived with individual traders, who may have started to make the journey in search of new markets despite the danger or the political situation of the time.

The Nature of the Route

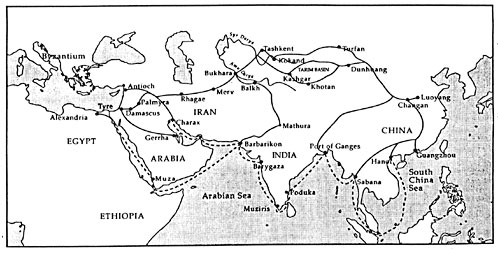

The description of this route to the west as the `Silk Road’ is somewhat misleading. Firstly, no single route was taken; crossing Central Asia several different branches developed, passing through different oasis settlements. The routes all started from the capital in Changan, headed up the Gansu corridor, and reached Dunhuang on the edge of the Taklimakan. The northern route then passed through Yumen Guan (Jade Gate Pass) and crossed the neck of the Gobi desert to Hami (Kumul), before following the Tianshan mountains round the northern fringes of the Taklimakan. It passed through the major oases of Turfan and Kuqa before arriving at Kashgar, at the foot of the Pamirs. The southern route branched off at Dunhuang, passing through the Yang Guan and skirting the southern edges of the desert, via Miran, Hetian (Khotan) and Shache (Yarkand), finally turning north again to meet the other route at Kashgar. Numerous other routes were also used to a lesser extent; one branched off from the southern route and headed through the Eastern end of the Taklimakan to the city of Loulan, before joining the Northern route at Korla. Kashgar became the new crossroads of Asia; from here the routes again divided, heading across the Pamirs to Samarkand and to the south of the Caspian Sea, or to the South, over the Karakorum into India; a further route split from the northern route after Kuqa and headed across the Tianshan range to eventually reach the shores of the Caspian Sea, via Tashkent.

Secondly, the Silk Road was not a trade route that existed solely for the purpose of trading in silk; many other commodities were also traded, from gold and ivory to exotic animals and plants. Of all the precious goods crossing this area, silk was perhaps the most remarkable for the people of the West. It is often thought that the Romans had first encountered silk in one of their campaigns against the Parthians in 53 B.C, and realised that it could not have been produced by this relatively unsophisticated people. They reputedly learnt from Parthian prisoners that it came from a mysterious tribe in the east, who they came to refer to as the silk people, `Seres’. In practice, it is likely that silk and other goods were beginning to filter into Europe before this time, though only in very small quantities. The Romans obtained samples of this new material, and it quickly became very popular in Rome, for its soft texture and attractiveness. The Parthians quickly realised that there was money to be made from trading the material, and sent trade missions towards the east. The Romans also sent their own agents out to explore the route, and to try to obtain silk at a lower price than that set by the Parthians. For this reason, the trade route to the East was seen by the Romans as a route for silk rather than the other goods that were traded. The name `Silk Road’ itself does not originate from the Romans, however, but is a nineteenth century term, coined by the German scholar, von Richthofen.

In addition to silk, the route carried many other precious commodities. Caravans heading towards China carried gold and other precious metals, ivory, precious stones, and glass, which was not manufactured in China until the fifth century. In the opposite direction furs, ceramics, jade, bronze objects, lacquer and iron were carried. Many of these goods were bartered for others along the way, and objects often changed hands several times. There are no records of Roman traders being seen in Changan, nor Chinese merchants in Rome, though their goods were appreciated in both places. This would obviously have been in the interests of the Parthians and other middlemen, who took as large a profit from the change of hands as they could.

The Development of the Route

The development of these Central Asian trade routes caused some problems for the Han rulers in China. Bandits soon learnt of the precious goods travelling up the Gansu Corridor and skirting the Taklimakan, and took advantage of the terrain to plunder these caravans. Caravans of goods needed their own defence forces, and this was an added cost for the merchants making the trip. The route took the caravans to the farthest extent of the Han Empire, and policing this route became a big problem. This was partially overcome by building forts and defensive walls along part of the route. Sections of `Great Wall’ were built along the northern side of the Gansu Corridor, to try to prevent the Xiongnu from harming the trade; Tibetan bandits from the Qilian mountains to the south were also a problem. Sections of Han dynasty wall can still be seen as far as Yumen Guan, well beyond the recognised beginning of the Great Wall at Jiayuguan. However, these fortifications were not all as effective as intended, as the Chinese lost control of sections of the route at regular intervals.

The Han dynasty set up the local government at Wulei, not far from Kuqa on the northern border of the Taklimakan, in order to `protect’ the states in this area, which numbered about 50 at the time. At about the same period the city of Gaochang was constructed in the Turfan basin. This developed into the centre of the Huihe kingdom; these peoples later became the Uygur minority who now make up a large proportion of the local population. Many settlements were set up along the way, mostly in the oasis areas, and profited from the passing trade. They also absorbed a lot of the local culture, and the cultures that passed them by along the route. Very few merchants traversed the full length of the road; most simply covered part of the journey, selling their wares a little further from home, and then returning with the proceeds. Goods therefore tended to moved slowly across Asia, changing hands many times. Local people no doubt acted as guides for the caravans over the most dangerous sections of the journey.

After the Western Han dynasty, successive dynasties brought more states under Chinese control. Settlements came and went, as they changed hands or lost importance due to a change in the routes. The chinese garrison town of Loulan, for example, on the edge of the Lop Nor lake, was important in the third century A.D., but was abandoned when the Chinese lost control of the route for a period. Many settlements were buried during times of abandonment by the sands of the Taklimakan, and could not be repopulated.

The settlements reflected the nature of the trade passing through the region. Silk, on its way to the west, often got no further than this region of Central Asia. The Astana tombs, where the nobles of Gaochang were buried, have turned up examples of silk cloth from China, as well as objects from as far afield as Persia and India. Much can be learned about the customs of the time from the objects found in these graves, and from the art work of the time, which has been excellently preserved on the tomb walls, due to the extremely dry conditions. The bodies themselves have also been well preserved, and may allow scientific studies to ascertain their origins.

The most significant commodity carried along this route was not silk, but religion. Buddhism came to China from India this way, along the northern branch of the route. The first influences came as the passes over the Karakorum were first explored. The Eastern Han emperor Mingdi is thought to have sent a representative to India to discover more about this strange faith, and further missions returned bearing scriptures, and bringing with them India priests. With this came influences from the Indian sub-continent, including Buddhist art work, examples of which have been found in several early second century tombs in present-day Sichuan province. This was considerably influenced by the Himalayan Massif, an effective barrier between China and India, and hence the Buddhism in China is effectively derived from the Gandhara culture by the bend in the Indus river, rather than directly from India. Buddhism reached the pastures of Tibet at a rather later period, not developing fully until the seventh century. Along the way it developed under many different influences, before reaching central China. This is displayed very cleared in the artwork, where many of the cave paintings show people with clearly different ethnic backgrounds, rather than the expected Cental and East Asian peoples.

The greatest flux of Buddhism into China occurred during the Northern Wei dynasty, in the fourth and fifth centuries A.D. This was at a time when China was divided into several different kingdoms, and the Northern Wei dynasty had its capital in Datong in present day Shanxi province. The rulers encouraged the development of Buddhism, and more missions were sent towards India. The new religion spread slowly eastwards, through the oases surrounding the Taklimakan, encouraged by an increasing number of merchants, missionaries and pilgrims. Many of the local peoples, the Huihe included, adopted Buddhism as their own religion. Faxian, a pilgrim from China, records the religious life in the Kingdoms of Khotan and Kashgar in 399 A.D. in great detail. He describes the large number of monasteries that had been built, and a large Buddhist festival that was held while he was there.

Some devotees were sufficiently inspired by the new ideas that they headed off in search of the source, towards Gandhara and India; others started to build monasteries, grottos and stupas. The development of the grotto is particularly interesting; the edges of the Taklimakan hide some of the best examples in the world. The hills surrounding the desert are mostly of sandstone, with any streams or rivers carving cliffs that can be relatively easily dug into; there was also no shortage of funds for the work, particularly from wealthy merchants, anxious to invoke protection or give thanks for a safe desert crossing. Gifts and donations of this kind were seen as an act of merit, which might enable the donor to escape rebirth into this world. In many of the murals, the donors themselves are depicted, often in pious attitude. This explains why the Mogao grottos contain some of the best examples of Buddhist artwork; Dunhuang is the starting point for the most difficult section of the Taklimakan crossing.

The grottos were mostly started at about the same period, and coincided with the beginning of the Northern Wei Dynasty. There are a large cluster in the Kuqa region, the best examples being the Kyzil grottos; similarly there are clusters close to Gaochang, the largest being the Bezeklik grottos. Probably the best known ones are the Mogao grottos at Dunhuang, at the eastern end of the Taklimakan. It is here that the greatest number, and some of the best examples, are to be found. More is known about the origins of these, too, as large quantities of ancient documents have been found. These are on a wide range of subjects, and include a large number of Buddhist scriptures in Chinese, Sanskrit, Tibetan, Uygur and other languages, some still unknown. There are documents from the other faiths that developed in the area, and also some official documents and letters that reveal a lot about the system of government at the time.

The grotto building was not confined to the Taklimakan; there is a large cluster at Bamiyan in the Hindu Kush, in present-day Afghanistan. It is here that the second largest sculpture of Buddha in the world can be found, at 55 metres high.

For the archaeologist these grottos are particularly valuable sources of information about the Silk Road. Along with the images of Buddhas and Boddhisatvas, there are scenes of the everyday life of the people at the time. Scenes of celebration and dancing give an insight into local customs and costume. The influences of the Silk Road traffic are therefore quite clear in the mix of cultures that appears on these murals at different dates. In particular, the development of Buddhism from the Indian/Gandharan style to a more individual faith is evident on studying the murals from different eras in any of the grotto clusters. Those from the Gandharan school have more classical features, with wavy hair and a sharper brow; they tend to be dressed in toga-like robes rather than a loin cloth. Those of the Northern Wei have a more Indian appearance, with narrower faces, stretched ear-lobes, and a more serene aura. By the Tang dynasty, when Buddhism was well developed in China, many of the statues and murals show much plumper, more rounded and amiable looking figures. By the Tang dynasty, the Apsara (flying deity, similar to an angel in Christianity) was a popular subject for the artists.

It is also interesting to trace the changes in styles along the length of the route, from Kuqa in the west, via the Turfan area and Dunhuang, to the Maijishan grottos about 350 kilometres from Xian, and then as far into China as Datong. The Northern Wei dynasty, that is perhaps the most responsible for the spread of Buddhism in China, started the construction of the Yungang grottos in northern Shanxi province. When the capital of the Northern Wei was transfered to Luoyang, the artists and masons started again from scratch, building the Longmen grottos. These two more `Chinese’ grottos emphasised carving and statuary rather than the delicate murals of the Taklimakan regions, and the figures are quite impressive in their size; the largest figure at Yungang measures more than 17 metres in height, second only in China to the great Leshan Buddha in Sichuan, which was constructed in the early 8th Century. The figures are mostly depicted in the `reassurance’ pose, with right hand raised, as an apology to the adherents of the Buddhist faith for the period of persecution that had occurred during the early Northern Wei Dynasty before construction was started.

The Buddhist faith gave birth to a number of different sects in Central Asia. Of these, the `Pure Land’ and `Chan’ (Zen) sects were particularly strong, and were even taken beyond China; they are both still flourishing in Japan.

Christianity also made an early appearance on the scene. The Nestorian sect was outlawed in Europe by the Roman church in 432 A.D., and its followers were driven eastwards. From their foothold in Northern Iran, merchants brought the faith along the Silk Road, and the first Nestorian church was consecrated at Changan in 638 A.D. This sect took root on the Silk Road, and survived many later attempts to wipe them out, lasting into the fourteenth century. Many Nestorian writings have been found with other documents at Dunhuang and Turfan. Manichaeism, a third century Persian religion, also influenced the area, and had become quite well developed by the beginning of the Tang Dynasty.

– The Silk Road – part 2/2

– Source www.ess.uci.edu/~oliver