Mogao Caves

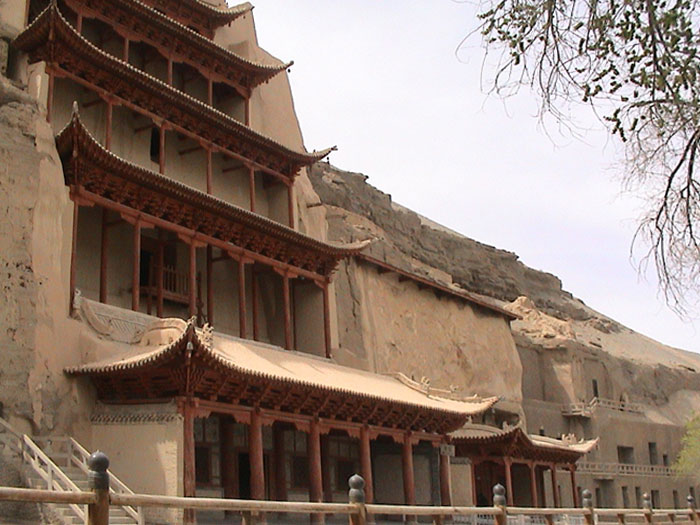

The Mogao Caves (aka Mogao Grottoes, Caves of the Thousand Buddhas, or Caves of Dunhuang) are a system of Buddhist cave temples near the city of Dunhuang in Gansu province. They were a center of culture on the Silk Road from the 4th to the 14th centuries and contain a religious artworks spanning that entire period. There are about 600 surviving cave temples, of which 30 are open to the public.

History

Before the arrival of Buddhism from India, temples in China (Taoist and Confucian) were made of wood, which was well adapted to most Chinese conditions. The tradition of cave temples originated in India, where poverty, lack of building material and intense heat had necessitated finding alternative methods to temple buildings.

The complex of cave temples emerged at Mogao in the 4th century, as pilgrims, monks and scholars passing on the Silk Road settled here to meditate and translate sutras. Merchants and nobles stopped here too, endowing temples to ensure the success of their business or to benefit their souls.

According to legend, the first cave was established in 366 AD by the Buddhist monk Lie Zun (or Lo-tsun), who had a vision of a thousand Buddhas. He convinced a wealthy Silk Road pilgrim to fund the first temple, and many followed his example. The murals were originally designed to assist devotional contemplation, but eventually acquired a narrative purpose as well.

Huge numbers of artists and craftsmen came to be employed at the caves, often lying on high scaffoldings and painting by the dim light of oil lamps. They usually lived in tiny caves in the northern section of the complex, sleeping on brick beds and paid only a pittance.

During the Tang dynasty, which saw Buddhism established throughout the Chinese empire, the monastic community reached its peak – more than a thousand cave temples were in operation. But thereafter, new sea routes gradually replaced the Silk Road and Mogao became increasingly provincial. Sometime in the 14th century, the caves were sealed and abandoned.

In 1900, a wandering Taoist monk named Wang Yuan Lu stumbled upon the Mogao Caves by accident. He immediately realized the significance of the site and made it his life’s work to excavate and restore the caves. He touched up the murals, planted trees and gardens, and built a guesthouse. The work was assisted by two acolytes and financed by begging expeditions.

This work might have continued in relative obscurity had it not been for an especially magnificent discovery. One day, Wang opened a bricked-up hidden chamber (cave #17), revealing an enormous collection of manuscripts, sutras and paintings on silk and paper. Some were 1,000 years old and virtually undamaged. It was one of the greatest archaeological discoveries of the 20th century.

News of the discovery reached the Dunhuang authorities, who appropriated a significant collection for themselves, then sealed the cave back up since it would be too expensive to transport the rest of the treasure. But in 1907, the explorer and scholar Aurel Stein arrived. A Hungarian working for the British, Stein persuaded Wang to reopen the chamber. He later recorded:

The sight the small room disclosed was one to make my eyes open; heaped up in layers, but without any order, there appeared in the dim light of the priest’s little lamp a solid mass of manuscript bundles rising to a height of nearly 10 feet and filling, as subsequent measurement showed, close on 500 cubic feet – an unparalleled archaeological scoop.

Among the collection were original sutras brought from India by the Tang monk Xuanzang, along with Buddhist texts written in Sanskrit, Sogdian, Tibetan, Runic-Turkic, Chinese, Uigur and other languages Stein could not identify. There were also dozens of rare Tang paintings on silk and paper – badly crushed by totally unaffected by damp.

Stein donated the equivalent of £130 to Wang’s restoration fund, then left for England with some 7,000 manuscripts and 500 paintings. Later in the year, a Frenchman by the name of Paul Pelliot negotiated a similar deal and shipped 6,000 manuscripts back to Paris. These still make up the bulk of the Chinese collections of the British Museum and the Louvre today.

The Mogao Caves were not declared a national monument until 1961, by which time they had suffered further damage – in 1920, a large party of White Russians used the caves as barracks and scrawled their names over the frescoes. But the art was not damaged during the Cultural Revolution; it is said they were protected on a personal order from Premier Zhou Enlai.

Today, the site is an important tourist attraction and the subject of an ongoing archaeological project. The Mogao Caves became a World Heritage Site in 1987. A fresh batch of 248 caves were located in 2001 and the artefacts they contained have yet to be fully assessed.

What to See

There were originally about 1,000 Buddhist cave temples here, over 600 of which survive in recognizable form. Many are off-limits, however, either because they are not of significant interest or they contain Tantric murals considered too sexually explicit for visitors.

Thirty main caves are open to the public, and most visitors manage to visit no more than fifteen in a day. The caves are all clearly labeled with numbers above the doors. They are not lit inside, in order to preserve the murals, but guides carry flashlights and visitors should bring their own as well.

Northern Wei Caves (386-581)

The early caves were carved out and decorated in the 4th and 5th centuries during the Northern Wei dynasty, which was founded by Turkic-speaking people known as the Tobas. There was constant friction within the dynasty between those who wanted to retain the ancient Toba customs and those who wanted to adapt Chinese customs.

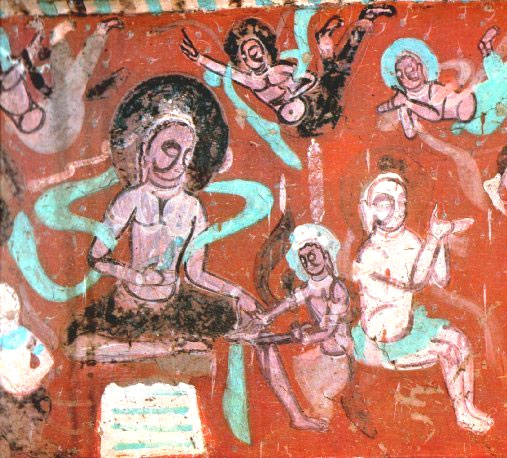

The Northern Wei caves tend to be small in size and supported in the center by a large column, a feature imported from India. There is usually a statue of the Buddha in the center, surrounded on the walls by tiers of many tiny Buddhas painted in black, white, blue, red and green. The statues are made of terracotta, as the soft rock of the caves was not suited to detailed carving.

The murals in the Northern Wei caves show a great deal of foreign influence – faces have long noses and curly hair and women are large-breasted. In cave 101, from the late 5th century, the Buddha is shown as a very western figure, quite Christ-like and reminiscent of Byzantine frescoes in Greece.

In cave 257, the Buddha seems to wear a Roman toga. Cave 428 shows strong Indian influence in both content (such as the peacocks on the ceiling) and style. But the beginnings of Chinese influence can also be seen in the wavy, flower-like angels that occasionally appear above.

The development from contemplation to narrative can be seen in these early caves, with stories depicted in long horizontal strips. Cave 135, from the early 6th century, illustrates a jataka story (from a former life of the Buddha) in which the Buddha gave his own body to feed a starving tigress so she could nurse her cubs. The narrative is read from right to left and is broken up by simple landscapes. Cave 254 shows the Buddha defeating Mara, or Illusion.

A more distinctive Chinese style emerged at the end of the Northern Wei period, around the mid-6th century. Among the most Chinese of the Wei murals is in cave 120N, which shows a series of battle scenes with a total lack of perspective – all figures are shown straight on, regardless of their relative positions. This was a favorite device in Chinese painting.

Sui Caves (581-618)

The Sui dynasty was short-lived but dynamic, and the caves of this period show a marked decrease in Western influences. There was a boom in Buddhism and Buddhist art in this period, and more than 70 caves were carved out at Mogao in the laste four decades.

The Sui caves dispense with the central column and replace the bold Wei brushwork with intricate, flowing lines and an increasingly extravagent use of color (including gold and silver). Statues become more stiff and inflexible and are dressed in Chinese robes.

In cave 150 (617 AD), narrative has been replaced with a repeated theme of enthroned Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. Cave 427 contains some characteristic Sui figures – short legs, long bodies (symbolizing power and divinity) and big, square heads.

Tang Caves (618-906)

The art of the Mogao Caves reached its peak under the Tang dynasty. Subjects drew on both past traditions and real life. The layout of a typical Tang cave temple consists of a square floor, tapering roof and niche for worship set into the back wall. The statuary now includes warriors and all figures are carefully detailed. The Bodhisattvas especially receive loving attention, with pleats and folds clinging softly to undulating feminine figures.

The Tang caves are famed for their Buddhas, which come in some astonishing sizes. Cave 96 contains a 34m-high seated Buddha, which is dressed in the dragon robe of the emperor and may have been intended to remind pilgrims of the Tang empress Wu Zetian. Cave 148 contains another huge Buddha, reclining on his death bed and surrounded by disciples.

Tang murals range from huge paintings depicting scenes from the sutras (contained in one composition instead of the long narrative strip of earlier dynasties) to vivid portraits of individuals.

One of the most popular Tang themes was that of the Visit of the Bodhisattva Manjusri to Vimalakirti, which is expressed most spectacularly in cave 1. Vimalakirti, on the left, is attended by a host of heavenly beings, eager to hear the discourse of the ailing old king. Above him is a seemingly limitless landscape, with the Buddha surrounded by Bodhisattvas on an island in the center. Another version can be seen in cave 51E, which is notable for the subtle shading in its portraits.

Other notable murals include a free, fluid landscape in cave 70 and a depiction of the Western Paradise of the Amitabha Buddha in cave 139A. In the latter, the souls of the reborn rise from lotus flowers in the foreground, with heavenly scenes enclosing the Buddha above.

Later Caves (906-c.1360)

Artwork at the Mogao Caves under the Five Dynasties, Song dynasty and Western Xia dynasty (906-1227) shows little development from the Tang caves, and mainly consists of restoration of existing murals. Work under the Song, however, is notable for a heavy richness of color and figures displaying the features of minority races.

During the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1260-1368), the standard niche in the back wall was replaced by a central altar, created uncluttered space for frescoes. Tibetan-style figures were introduced and mandalas were among the mural subjects. The most interesting example is cave 465, which a guide might open for you for a very large fee – the murals include Tantric figures in the ultimate state of enlightenment, symbolically represented by the state of sexual union.

Quick Facts

Names: Mògao Shíku; Mogao Caves; Caves of the Thousand Buddhas; Mogao Grottoes;

Caves of Dunhuang

Type of site: Cave temples

Faith: Buddhism

Status: Museum

Dates: 4th-14th century

Architecture/Art: Northern Wei; Tang; others

Location: 25km SE of Dunhuang

Hours: 8:10am – 6pm

Cost: ¥80; half-day tour with English-speaking guide ¥120

Photography: Cameras not allowed in caves without a very expensive photo permit.

Getting There

Minibuses leave from Feitian Binguan at 8am (30 min.; ¥8/$1 one-way, ¥10/$1.25 round-trip); or you catch a minibus on Xin Jiàn Lù for a similar fare. In peak season these fill up quickly, but in the off season, you will get a free tour of Dunhuáng. If you plan to spend only a half-day at Mògao Shíku, get there as early as possible; buses return to Dunhuáng at noon. Afternoon buses return at 6pm.

– source Sacred Destinations

– WHTour.org : visit this site in panographies (360 degree imaging)