Features

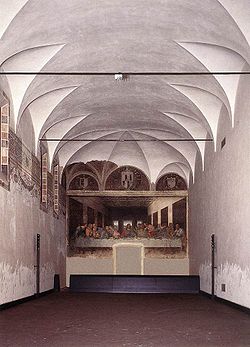

The painting measures 460 × 880 centimeters (15 feet × 29 ft) and covers the back wall of the dining hall at Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy. The theme was a traditional one for refectories, but Leonardo’s interpretation gave it much greater realism and depth. The lunettes above the main painting, formed by the triple arched ceiling of the refectory, are painted with Sforza coats-of-arms. The opposite wall of the refectory is covered by the Crucifixion fresco by Giovanni Donato da Montorfano, to which Leonardo added figures of the Sforza family in tempera. (These figures have deteriorated in much the same way as has The Last Supper.) Leonardo began work on The Last Supper in 1495 and completed it in 1498—however, he did not work on the piece continuously throughout this period. This beginning date is not certain, as “the archives of the convent have been destroyed and our meagre documents date from 1497 when the painting was nearly finished.”

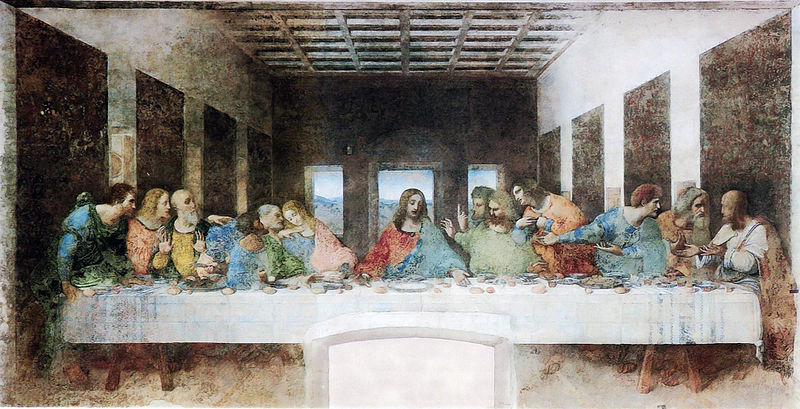

The Last Supper specifically portrays the reaction given by each apostle when Jesus said one of them would betray him. All twelve apostles have different reactions to the news, with various degrees of anger and shock. From left to right:

Bartholomew, James, son of Alphaeus and Andrew form a group of three, all are surprised.

Judas Iscariot, Peter and John form another group of three. Judas is wearing green and blue and is in shadow, looking rather withdrawn and taken aback by the sudden revelation of his plan. He is clutching a small bag, perhaps signifying the silver given to him as payment to betray Jesus, or perhaps a reference to his role within the 12 disciples as treasurer. He is the only person to have his elbow on the table; traditionally a sign of bad manners. Peter looks angry and is holding a knife pointed away from Christ, perhaps foreshadowing his violent reaction in Gethsemane during Jesus’ arrest. The youngest apostle, John, appears to swoon.

Thomas, James the Greater and Philip are the next group of three. Thomas is clearly upset; James the Greater looks stunned, with his arms in the air. Meanwhile, Philip appears to be requesting some explanation.

Matthew, Jude Thaddeus and Simon the Zealot are the final group of three. Both Jude Thaddeus and Matthew are turned toward Simon, perhaps to find out if he has any answer to their initial questions.

These names are all agreed upon by art historians. In the 19th century, a manuscript (The Notebooks Leonardo Da Vinci pg. 232) was found with their names; before this only Judas, Peter, John and Jesus were positively identified.

In common with other depictions of The Last Supper from this period, Leonardo adopts the convention of seating the diners on one side of the table, so that none of them have their backs to the viewer. However, most previous depictions had typically excluded Judas by placing him alone on the opposite side of the table from the other eleven disciples and Jesus. Another technique commonly used was placing halos around all the disciples except Judas. Leonardo creates a more dramatic and realistic effect by having Judas lean back into shadow. He also creates a realistic and psychologically engaging means to explain why Judas takes the bread at the same time as Jesus, just after Jesus has predicted that this is what his betrayer will do. Jesus is shown saying this to Saints Thomas and James to his left, who react in horror as Jesus points with his left hand to a piece of bread before them. Distracted by the conversation between John and Peter, Judas reaches for a different piece of bread, as, unseen by him, Jesus too stretches out with his right hand towards it. (Matthew 26: 17-46). The angles and lighting draw attention to Jesus, whose head is located at the vanishing point for all perspective lines.

The painting contains several references to the number 3, which may be an allusion to the Holy Trinity. The Apostles are seated in groupings of three; there are three windows behind Jesus; and the shape of Jesus’ figure resembles a triangle. There may have been many other references that have since been lost to the painting’s deterioration.

Medium

Two early copies of The Last Supper are known to exist, presumably the work of Leonardo’s assistant. The copies are almost the size of the original, and have survived with a wealth of original detail still intact.

Damage and restorations

As early as 1517 the painting was starting to flake. By 1556—less than sixty years after it was finished — Leonardo’s biographer Giorgio Vasari described the painting as already “ruined” and so deteriorated that the figures were unrecognizable. In 1652 a doorway was cut through the (then unrecognisable) painting, and later bricked up; this can still be seen as the irregular arch shaped structure near the center base of the painting. It is believed, through early copies, that Jesus’ feet were in a position symbolizing the forthcoming crucifixion. In 1768 a curtain was hung over the painting for the purpose of protection; it instead trapped moisture on the surface, and whenever the curtain was pulled back, it scratched the flaking paint.

A first restoration was attempted in 1726 by Michelangelo Bellotti, who filled in missing sections with oil paint then varnished the whole mural. This repair did not last well and another restoration was attempted in 1770 by Giuseppe Mazza. Mazza stripped off Bellotti’s work then largely repainted the painting; he had redone all but three faces when he was halted due to public outrage. In 1796 French troops used the refectory as an armory; they threw stones at the painting and climbed ladders to scratch out the Apostles’ eyes. The refectory was then later used as a prison; it is not known if any of the prisoners may have damaged the painting. In 1821 Stefano Barezzi, an expert in removing whole frescoes from their walls intact, was called in to remove the painting to a safer location; he badly damaged the centre section before realising that Leonardo’s work was not a fresco. Barezzi then attempted to reattach damaged sections with glue. From 1901 to 1908, Luigi Cavenaghi first completed a careful study of the structure of the painting, then began cleaning it. In 1924 Oreste Silvestri did further cleaning, and stabilised some parts with stucco.

During World War II, on August 15, 1943, the refectory was struck by a bomb; protective sandbagging prevented the painting from being struck by bomb splinters, but it may have been damaged further by the vibration. From 1951 to 1954 another clean-and-stabilise restoration was undertaken by Mauro Pelliccioli.

The painting’s appearance in the late 1970s was badly deteriorated and unrecognizable. From 1978 to 1999 Pinin Brambilla Barcilon guided a major restoration project which undertook to permanently stabilize the painting, and reverse the damage caused by dirt, pollution, and the misguided 18th and 19th century restoration attempts. Since it had proved impractical to move the painting to a more controlled environment, the refectory was instead converted to a sealed, climate controlled environment, which meant bricking up the windows. Then, detailed study was undertaken to determine the painting’s original form, using scientific tests (especially infrared reflectoscopy and microscopic core-samples), and original cartoons preserved in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle. Some areas were deemed unrestorable. These were re-painted with watercolour in subdued colours intended to indicate they were not original work, whilst not being too distracting.

This restoration took 21 years and on May 28, 1999 the painting was put back on display, although intending visitors are required to book ahead and can only stay for 15 minutes. When it was unveiled, considerable controversy was aroused by the dramatic changes in colours, tones, and even some facial shapes. James Beck, professor of art history at Columbia University and founder of ArtWatch International, had been a particularly strong critic.

Rumours and alternative theories

A common rumour surrounding the painting is that the same model was used for both Jesus and Judas. The story often goes that the innocent-looking young man, a baker, posed at nineteen for Jesus. Some years later Leonardo discovered a hard-bitten criminal as the model for Judas, not realizing he was the same man. There is no evidence that Leonardo used the same model for both figures and the story usually overestimates the time it took Leonardo to finish the mural. Some writers identify the person to Jesus’ right not with the Apostle John (as is supposed by icongraphical tradition and confirmed by art historians) but with Mary Magdalene. This theory was the topic of the book The Templar Revelation, and plays a central role in Dan Brown’s novel The Da Vinci Code (2003).

Critics of these theories will point out that:

Leonardo was requested to paint the Last Supper, which naturally included Jesus and his Twelve Apostles. As there are only thirteen figures in the painting, an apostle would have been missing to make way for Mary Magdalene. Somebody would have noted a missing male apostle earlier. Some have suggested that on the front of the figure of Simon Peter there is one hand with a dagger which is associated to nobody in the picture, but in clearer reproductions this is seen to be Peter’s right hand, resting against his hip with the palm turned outward; the knife points towards Bartholomew (far left) who was to be executed by being flayed. It may also indicate Peter’s impulsive nature, as he cuts off a soldier’s ear in John 18:10. A detailed preliminary drawing of the arm exists.

The figure in question is wearing male clothing.

Some of the painting’s cartoons (preliminary sketches) are preserved, and none show female faces.

Other paintings from that period (Castagno’s 1447 and Ghirlandaio’s 1480) also show John to be a very boyish or feminine looking figure with long fair hair.This was because John was supposed to have been the youngest and most unquestioningly devoted of the apostles. Hence he is often shown asleep against Jesus’s shoulder. It was common in the period to show neophytes as very young or even feminine figures, as a way of showing their inferior position.

Leonardo also portrayed a male saint with similar effeminate features in his painting St. John the Baptist.

There have also been other popular speculations about the work:

It has been suggested that there is no cup in the painting, yet Jesus’ left hand is pointing to the Eucharist and his right to a glass of wine. (There are several glasses on the table, but they are difficult to see owing to the work’s deterioration and restorations.) This is not the glorified chalice of legend as Leonardo insisted on realistic paintings. He often criticised Michelangelo for painting muscular, superhuman figures in the Sistine Chapel.

It is claimed that if one looks above the figure of Bartholemew, a Grail-like image appears on the wall. Whether Leonardo meant this to be a representation of the Holy Grail cannot be known, since as pointed out earlier there is a glass on the table within Christ’s reach. The “Grail image” has become noticed probably because it only appears when viewing the painting in small scale reproductions. Zooming in on the painting reveals a cluster of geometrical shapes, possibly intended to represent marble wall decoration, or more likely, paneling on a door.They only appear to form a golden chalice when parts are deliberately occluded.

Slavisa Pesci, “an information technologist and amateur scholar”, superimposed Leonardo da Vinci’s version of The Last Supper with its mirror image (with both images of Jesus lined up) and claimed that the resultant picture has:

a Templar knight on the far left

a woman in orange holds a swaddled babe in arms to the left of Christ

the Holy Grail used in the first Eucharist

Giovanni Maria Pala, an Italian musician, has indicated that the positions of hands and loaves of bread can be interpreted as notes on a musical staff, and if read from right to left, as was characteristic of Da Vinci’s writing, form a musical composition.

The Last Supper in culture

Painting, mosaic and photography

A fine 16th century oil on canvas copy is conserved in the abbey of Tongerlo, Antwerp, Belgium. It reveals many details that are no longer visible on the original. The Roman mosaic artist Giacomo Raffaelli made another life-sized copy (1809-1814) in the Viennese Minoritenkirche.

In 1955, the renowned artist Salvador Dali painted The Sacrament of the Last Supper, with Jesus portrayed as blonde and clean shaven, pointing upward to a spectral torso while the apostles are gathered around the table heads bowed so that none may be identified. It has been generally considered a masterpiece, and is reputed to be one of the most popular paintings in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

In more recent times, the painting has also been much imitated and parodied in art and photography. Mary Beth Edelson’s “Some Living American Women Artists/Last Supper” (1971) reproduced the composition with Georgia O’Keeffe in the central position. Likewise, Yo Mama’s Last Supper, a controversial work of art by Renée Cox, was a montage of five photographs of twelve black men and a naked black woman (the artist’s self portrait) posed in imitation of Leonardo’s painting. Cox is pictured naked and standing, with her arms reaching upwards, as Jesus. The piece is exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, and received acclaim and criticism in heavy measure, the latter notably by former mayor of New York City, Rudy Giuliani.

In 2003, when pop star Michael Jackson’s Neverland Ranch was raided in a search for evidence regarding child molestation charges, a pastiche of The Last Supper was found. It depicts a similar scene, except this one has Jackson posing in the position of Jesus, with the apostles replaced by great creative figures of history. It hangs above Jackson’s bed in his private quarters.

Modern art

In 1988, modern artist Vik Muniz famously displayed a recreation of The Last Supper, made entirely out of Bosco Chocolate Syrup.

In 2007, Pennsylvania artist Mark Beekman created the world’s largest Lite-Brite of The Last Supper, breaking the record held by the previous Guinness record holder for largest Lite-Brite object. As of December 2007, the object was being auctioned on eBay.

On 30 July 2008 “The Last Supper” was the subject of an animation by British film-maker, Peter Greenaway, who projected interpretative images onto its surface to bring the scene to life. His plans to do so had faced criticism and concerns that it would damage the work, but eventually went ahead when the proviso was given that the show would only occur once. He plans to replicate it in a more permanent form onto a full-size reproduction of the painting in a British gallery, and to carry out similar shows on Las Meninas by Velázquez, Picasso’s Guernica, Monet’s Waterlilies, a Jackson Pollock painting in New York and Michelangelo’s Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel.