ASOKA or ASHOKA

KING and EMPEROR

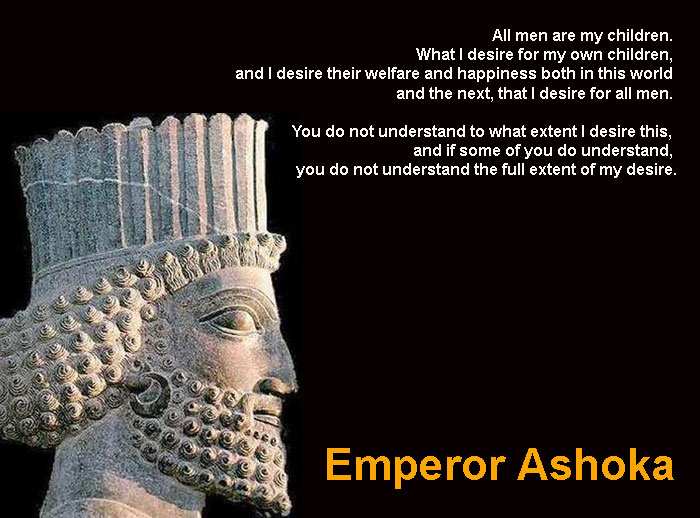

EMPEROR ASHOKA

273 – 232 BC

In the history of the world there have been thousands of kings and emperors who called themselves ‘Their Highnesses’, ‘Their Majesties’ and ‘Their Exalted Majesties’ and so on. They shone for a brief moment, and as quickly disappeared. But Ashoka shines and shines brightly like a bright star, even unto this day. So wrote H.G. Wells, British historian and noble seeker of the truth about mankind’s tumultuous past.

Questionable Hereditary Succession

Ashoka was anointed the new emperor or ruler of the Mauryan Empire in 274 BCE. His grandfather, Chandragupta, had set out to conquer the weaker surrounding kingdoms to expand the territory of his people in 324 BCE, and was the first to rule over a unified India. Ashoka’s father, Bindusara, established a reign much the same as his father’s, controlling a larger kingdom than ever before known. When Bindusara became gravely ill, Ashoka succeeded him, although one hundred of his other brothers were mysteriously murdered. Many historians believe Ashoka had his own brothers eliminated so that he could succeed his father.

A Sudden Change of Heart

Ashoka’s reign as emperor began with a series of wars and bloodshed, culminating in the Kalinga War of 260 BC. The mammoth loss of life and suffering witnessed on the battlefield made him turn away from war. He subsequently became deeply influenced by Buddhism, and adopted the dharma, which consists of basic virtuous teachings that can be practiced by all men regardless of social origins. “Dharma” is derived from the Sanskrit word for “duty”.

Towards a New Imperial Unity

Ashoka saw the dharma as a righteous path showing the utmost respect for all living things. The dharma would bring harmony and unity to India in the form of much needed compassion. Serving as a guiding light, a voice of conscious that is the dharma can lead one to be a respectful and highly responsible human being. Edward D’cruz interprets the Ashokan dharma as a “religion to be used as a symbol of a new imperial unity and a cementing force to weld the diverse and heterogeneous elements of the empire”. Ashoka’s intent was to instigate “a practice of social behavior so broad and benevolent in its scope, that no person, no matter what his religion, could reasonably object to it”.

The Moral Order of Dharma

Ashoka’s dream was to unify a nation so large that its people of one region shared little in common with those of another region. Diversity of religion, ethnicity and many cultural aspects held citizens against each other, creating social barriers. The moral order of dharma could be agreed upon as beneficial and progressive by all who could understand its merits; in fact, the dharma had long been a primary practice for members of Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism. Dharma became the link between king and commoner; everyone lived by the same law of moral, religious and civil obligations towards others.

Pillars of the Earth

The reign of Ashoka Mauryan could easily have disappeared into history as the ages passed by, and would have, if hadn’t he left behind a record of his trials. The testimony of this wise king was discovered in the form of magnificently sculpted pillars and boulders with the various actions and teachings he wished to be published etched into the stone. What Ashoka left behind was the first written language in India since the ancient city of Harrapa. Rather than Sanskrit, the language used for inscription was the current spoken form called Prakrita. In translating these monuments, historians learn the bulk of what is assumed to have been true fact of the Mauryan Empire. It is difficult to determine whether or not some actual events ever happened, but the stone etchings clearly depict how Ashoka wanted to be thought of and remembered.

The Emperor’s New Edicts

King Ashoka, the third monarch of the Indian Mauryan dynasty, has come to be regarded as one of the most exemplary rulers in world history. Although Buddhist literature preserved the legend of this ruler – the story of a cruel and ruthless king who converted to Buddhism and thereafter established a reign of virtue – definitive historical records of his reign were lacking. Then in the nineteenth century there came to light a large number of edicts, in India, Nepal, Pakistan and Afghanistan. These edicts, inscribed on rocks and pillars, proclaim Asoka’s reforms and policies and promulgate his advice to his subjects. The present rendering of these edicts, based on earlier translations, offers us insights into a powerful and capable ruler’s attempt to establish an empire on the foundation of righteousness, a reign which makes the moral and spiritual welfare of his subjects its primary concern.

Beyond Greed, Hatred and Delusion

We have no way of knowing how effective Ashoka’s reforms were or how long they lasted, but we do know that monarchs throughout the ancient Buddhist world were encouraged to look to his style of good government as an ideal to be venerated and kindredly administered. King Ashoka undoubtedly has to be credited with the first serious attempt to develop a Buddhist polity. Today, with widespread disillusionment in prevailing ideologies, and the search for a political philosophy that goes beyond greed (capitalism), hatred (communism) and delusion (dictatorships led by “infallible” leaders), Asoka’s edicts may still make a meaningful contribution to the development of a more spiritually-based political system of good government for every nation on earth.

A Well Respected Man

Emperor Ashoka was a cruel and merciless ruler at first. He waged war on his perceived enemies on a whim, and caused much suffering amongst his own people. While observing a massive slaughter at the front lines of his army, he experienced a change of heart and turned to the welfare of his own people, who still justly feared him as a ruthless and highly oppressive tyrant. Somewhere along the way he had become a Buddhist, and as a result taught and persuaded his people to love and respect all living things. He insisted on the recognition of the sanctity of all human life. The horrors of war have often transformed savage hearts into compassionate ones. Even the unnecessary slaughter or mutilation of animals was immediately abolished. Wildlife became protected by the king’s law against sport hunting and branding. Limited hunting was permitted for consumption reasons but the overwhelming majority of Indians chose by their own free will to become vegetarians. Ashoka also showed mercy to those imprisoned, allowing them leave for the outside a day of the year. He attempted to raise the professional ambition of the common man by building universities for study and water transit and irrigation systems for trade and agriculture. He treated his subjects as equals regardless of their religion, politics and cast. The kingdoms surrounding his, so easily overthrown, were instead made to be well-respected allies.

In His Own Words

All men are my children. I am like a father to them. As every father desires the good and the happiness of his children, I wish that all men should be happy always.

Coda

During his reign, Ashoka became an avid Buddhist practitioner, building 84,000 stupas across his empire to house the sacred relics of the Lord Buddha. He sent his family on religious pilgrimages to foreign places, and staged massive assemblies so holy men from the world over could converse upon the philosophies of the day. More than even Buddhism was Ashoka’s deep involvement in the dharma. The dharma became the ultimate expression of the moral and ethical standards he desired his subjects to live by. Ashoka defined the main principles of dharma (dhamma) as nonviolence, tolerance of all sects and opinions, obedience to parents, respect for the Brahmans and other religious teachers and priests, liberality towards friends, humane treatment of servants, and generosity towards all. These principles suggest a general ethic of behaviour to which no religious or social group could object.

Rock On

In perhaps a fitting tribute to this great man of vision and unity, the Indian government has adopted the famous lion capital from his pillar at Sarnath as its official national emblem. The wheel design on the capital’s base has also become the central figure of the nation’s flag. May the wheel keep on turning for the sake of all men who are brothers in this brave new millennium of ours, and may the teachings of the Light of Asia continue to reach every corner of the earth despite what some inferior men may do or say.

– Source : blogs.ibibo.com

Ashoka – Buddhist Conversion

As the legend goes, one day after the war was over, Ashoka ventured out to roam the city and all he could see were burnt houses and scattered corpses. This sight made him sick and he cried the famous quote, “What have I done?” The brutality of the conquest led him to adopt Buddhism and he used his position to propagate the relatively new philosophy to new heights, as far as ancient Rome and Egypt. He made Vibhajyavada Buddhism his state religion around 260 BC. He propagated the Vibhajyavada school of Buddhism and preached it within his domain and worldwide from about 250 BC. Emperor Ashoka undoubtedly has to be credited with the first serious attempt to develop a Buddhist polity.

Prominent in this cause were his son Venerable Mahinda and daughter Sanghamitta (whose name means “friend of the Sangha”), who established Buddhism in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). He built thousands of Stupas and Viharas for Buddhist followers. The Stupas of Sanchi are world famous and the stupa named Sanchi Stupa was built by Emperor Ashoka.

During the remaining portion of Ashoka’s reign, he pursued an official policy of nonviolence, ahimsa. Even the unnecessary slaughter or mutilation of animals was immediately abolished. Wildlife became protected by the king’s law against sport hunting and branding. Limited hunting was permitted for consumption reasons but Ashoka also promoted the concept of vegetarianism. Ashoka also showed mercy to those imprisoned, allowing them leave for the outside a day of the year.

He attempted to raise the professional ambition of the common man by building universities for study and water transit and irrigation systems for trade and agriculture. He treated his subjects as equals regardless of their religion, politics and caste. The kingdoms surrounding his, so easily overthrown, were instead made to be well-respected allies.

He is acclaimed for constructing hospitals for animals and renovating major roads throughout India. After this transformation of self, Ashoka came to be known as Dhammashoka (Sanskrit), meaning Ashoka, the follower of Dharma. Ashoka defined the main principles of dharma (dhamma) as nonviolence, tolerance of all sects and opinions, obedience to parents, respect for the Brahmans and other religious teachers and priests, liberality towards friends, humane treatment of servants, and generosity towards all. These principles suggest a general ethic of behaviour to which no religious or social group could object.

Some critics say that Ashoka was afraid of more wars, but among his neighbors, including the Seleucid Empire and the Greco-Bactrian kingdom established by Diodotus I, none could match his strength. He was a contemporary of both Antiochus I Soter and his successor Antiochus II Theos of the Seleucid dynasty as well as Diodotus I and his son Diodotus II of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. If his inscriptions and edicts are well studied, one finds that he was familiar with the Hellenic world but never in awe of it. His edicts, which talk of friendly relations, give the names of both Antiochus of the Seleucid empire and Ptolemy III of Egypt. But the fame of the Mauryan empire was widespread from the time that Ashoka’s grandfather Chandragupta Maurya defeated Seleucus Nicator , the founder of the Seleucid Dynasty.

The source of much of our knowledge of Ashoka is the many inscriptions he had carved on pillars and rocks throughout the empire. Emperor Ashoka is known as Piyadasi (in Pali) or Priyadarshi (in Sanskrit) meaning “good looking” or “favoured by the gods with good blessing”. All his inscriptions have the imperial touch and show compassionate loving; he addressed his people as his “children”. These inscriptions promoted Buddhist morality and encouraged nonviolence and adherence to Dharma (duty or proper behavior), and they talk of his fame and conquered lands as well as the neighbouring kingdoms holding up his might. One also gets some primary information about the Kalinga War and Ashoka’s allies plus some useful knowlege on the civil admisistration. The Ashoka Pillar at Sarnath is the most popular of the relics left by Ashoka. Made of sandstone, this pillar records the visit of the emperor to Sarnath, in the 3rd century BC. It has a four-lion capital (four lions standing back to back) which was adopted as the emblem of the modern Indian republic. The lion symbolises both Ashoka’s imperial rule and the kingship of the Buddha. In translating these monuments, historians learn the bulk of what is assumed to have been true fact of the Mauryan Empire. It is difficult to determine whether or not some actual events ever happened, but the stone etchings clearly depict how Ashoka wanted to be thought of and remembered.

Ashoka’s own words as known from his Edicts are: “All men are my children. I am like a father to them. As every father desires the good and the happiness of his children, I wish that all men should be happy always.” Edward D’Cruz interprets the Ashokan dharma as a “religion to be used as a symbol of a new imperial unity and a cementing force to weld the diverse and heterogeneous elements of the empire”.

At the time of Emperor Ashoka (270-232 BC), according to his Edicts.

Also, in the Edicts of Ashoka, Ashoka mentions the Hellenistic kings of the period as a convert to Buddhist, although no Hellenic historical record of this event remain:

The conquest by Dharma has been won here, on the borders, and even six hundred yojanas (5,400-9,600 km) away, where the Greek king Antiochos rules, beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy, Antigonos, Magas and Alexander rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni (Sri Lanka).

Ashoka also claims that he encouraged the development of herbal medicine, for human and nonhuman animals, in their territories:

- Everywhere within Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi’s [Ashoka’s] domain, and among the people beyond the borders, the Cholas, the Pandyas, the Satiyaputras, the Keralaputras, as far as Tamraparni and where the Greek king Antiochos rules, and among the kings who are neighbors of Antiochos, everywhere has Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi, made provision for two types of medical treatment: medical treatment for humans and medical treatment for animals. Wherever medical herbs suitable for humans or animals are not available, I have had them imported and grown. Wherever medical roots or fruits are not available I have had them imported and grown. Along roads I have had wells dug and trees planted for the benefit of humans and animals.

- Ashoka the Great, Edicts of Ashoka, Rock Edict 2

The Greeks in India even seem to have played an active role in the propagation of Buddhism, as some of the emissaries of Ashoka, such as Dharmaraksita, are described in Pali sources as leading Greek (“Yona”) Buddhist monks, active in spreading Buddhism (the Mahavamsa, XII).

Comments are closed.