HELPING THE HELPLESS

March 31, 2008

MUMBAI, India – A SRI Lankan monk was in a crowded train travelling from Mumbai to Ulhasnagar in India, in 1982. A couple of superior caste members were seated comfortably, while several labourers were standing nearby. When a labourer accidentally brushed against a woman’s shoulders, the husband took offence and beat him up.

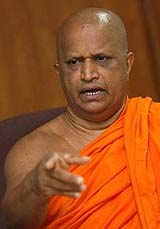

<< Ven Dr Talawe Sangharatana Thera: ‘We want to help India as it is the Land of Buddha.’

<< Ven Dr Talawe Sangharatana Thera: ‘We want to help India as it is the Land of Buddha.’

In 1995, the monk, Ven Dr Talawe Sangharatana Thera, was on the platform of a train station in New Delhi. “A young boy who was begging for food was chased away by members of a higher class. When he approached me, I gave him some money and heard them remarking that ‘Only beggars help beggars.’

“These (condescending) folks probably believe that God created beggars to teach them the meaning of poverty. As such, they do not want to help these unfortunate ones,” said Ven Sangharatana, chief monk of Pitaramba Temple in Bentota, Sri Lanka, during a recent visit to Malaysia.

In another incident in a New Delhi university, he saw a boy being beaten up for courting a girl from a higher caste. “No one came to his aid and when the police arrived, they took the boy away instead of his attackers,” said Ven Sangharatana, 60.

Such centuries-old discrimination against the Untouchables left an indelible mark on the monk.

In 1982, Ven Sangharatana headed for Maharashtra in Western India because the majority of Untouchables were found in this state. Maharashtra was the birthplace of the late Dr B.R. Ambedkar, a great leader of the Untouchables and “the father of modern Buddhism”. Ambedkar later went on to become the first Minister of Law in India.

“We want to help India as it is the Land of Buddha,” said Ven Sangharatana, adding that Ambedkar had called upon monks from abroad to help his community (the Untouchables) by giving them education, helping them to rebuild their society and teaching them basic hygiene.

“Today, the Indian government welcomes those who want to help the Untouchables. The Hindus are happy to see us as social workers. We don’t help only the Buddhists but also the poor Muslims and Christians in the community.”

Every year, the foundation distributes stationery to needy schoolchildren. Last year, it launched a micro-credit programme to offer interest-free loans to women to start their own businesses such as selling vegetables, sewing garments and making toys and shoes. The loans have to be repaid in instalments within a year.

Dalit children playing in a broken house on the outskirts of the city of Lucknow in India >>

In January this year, he started a foster parent project in Bangalore. Under this programme, needy schoolchildren receive financial aid on a monthly basis.

Last December, Ven Sangharatana visited Bidar, a rural area with a majority of Untouchables who are Buddhists, on a request to set up a training centre for monks and a school. The journey to Bidar from Bangalore took more than 14 hours by bus through rough terrain.

“I was asked to find financial support for them,” he said, adding that he was appointed the community’s patron.

When he was in India, Ven Sangharatana donned helmet and mask before going 91m down a mineshaft to experience the poor working conditions of miners. He also witnessed ill treatment of the Untouchables.

Some say the Untouchables or Scheduled Caste still suffer from an inferiority complex due to their background. People could tell if they were from the lower caste just by their family names, the areas they come from and their behaviours, said Ven Sangharatana.

“Buddhism is against the caste system. Everyone is equal. We should respect every human being and every religion.”

In his book, Buddhists in Maharashtra (published in 2001), Ven Sangharatana wrote about how the caste problem prevailed in Maharashtra. The issue of Untouchability made social depression rampant down the centuries, creating mental and physical oppression of the downtrodden.

<< Lucknow’s Dalit women working with cow dung.

<< Lucknow’s Dalit women working with cow dung.

According to Ven Sangharatana, since the third century AD, the early caste system was divided into Brahmins, Vaisyas, Ksatriyas and Sudras. Later, society created another caste – the outcaste – and historians believe that this caste appeared due to the Renaissance of Hinduism. In the Indian caste system, a Dalit or Untouchable is a person who, according to traditional Hindu belief, does not have any varnas.

Varna refers to the Hindu belief that most humans were supposedly created from different parts of the body of the divinity Purusha. The part from which a varna was supposedly created defines a person’s social status.

Dalits fall outside the varna system and have historically been prevented from doing any but the most menial jobs. Among them are leather-workers (called chamar), carcass handlers (mahar), farmers and landless labourers, night soil scavengers (bhangi or chura), handicraft-makers, folk artists, street cleaners and dhobi.

There are an estimated 160 million Dalits in India. Traditionally, they are treated as pariahs in South Asian society and isolated in their own communities. Even their shadows are avoided by the upper castes.

Discrimination against Dalits still exists in some rural areas. In urban areas and in the public sphere, such discrimination has largely disappeared following access to better education.

Champion of the Dalits

THE Untouchables in Hindu society were a helpless lot. They were denied the use of public wells and shut out from Hindu temples and festivals. They were generally landless and had to live in the outskirts of villages due to social threats.

Thankfully, they found a champion.

“B.R. Ambedkar was born into this community and met with many social problems since childhood. However, he struggled to change these social differences and delivered his people,” said Ven Dr Talawe Sangharatana Thera in his book, Buddhists in Maharashtra.

Ambedkar read about all the religions in the world and decided to become a Buddhist. He opened his people’s eyes to a new religion that could set them free.

“Ambedkar met with other leaders of the Untouchables and together they wanted to change social discrimination against them. Failing to get the British to help, Ambedkar decided that the best recourse would be to change their religion since they were forbidden to enter a temple for worship. The temple owners also did not want the Untouchables to tread on holy ground and contaminate the place,” related Ven Sangharatana.

A Dalit woman in Lucknow. >>

A Dalit woman in Lucknow. >>

In 1956, Ambedkar together with 5,000 followers embraced Buddhism in a mass conversion. This event in Nagpur on Oct 14 was a historical day for the Untouchables of India.

“Ambedkar explained that he was not out to seek any economic gain by embracing a new religion. He wanted happiness with social dignity. He saw that freedom, equality and brotherhood were available in Buddhism,” said Ven Sangharatana.

In his book, Annihilation of Caste, Ambedkar explained the history of the Brahmins and how they built their citadel in Indian society. He accused this caste of monopolising social privileges, education and religion, and depriving the poor in India. He was intent to wipe out the caste system.

“Ambedkar became the father of the oppressed and brought Buddhism back to life in India,” said Ven Sangharatana.

To see the propagation of Buddhism in India, Ambedkar worked tirelessly until he passed away on Dec 6, 1956, at the age of 65. Even after his death, great waves of conversion took place in Maharashtra as his followers carried on the propagation work. About 30,000 Untouchables were said to join the fold of Buddhism in a short span of time.

And so, Maharashtra, the home state of Ambedkar, has the largest Buddhist population in India.

By Majorie Chiew

Source : The Star