The Buddha at Kamakura

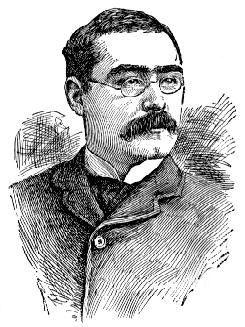

by Rudyard Kipling

Big Buddha in Kamakura

Constructed in 1252. Of the three giant effigies of Buddha in Japan, it alone remains in orginal form, whereas the 8th-century 72-feet-high statue in Nara was recast, and the famous 160-feet-high Kyoto Daibutsu was entirely destroyed and replaced by a small wooden substitute.

Located at Koutokuin 高徳院 in Kamakura, the Kamakura Daibutsu (literally “Kamakura Big Buddha”) is a giant metal statue of Amida Nyorai. Roughly 15 meters in height (the face itself nearly 2.5 meters long), this statue weighs 93 tons. Upon the head are 656 hair curls, a traditional characteristic of the Amida Buddha. The silver boss on the forehead (from which emanates the light that illuminates the universe) weighs 30 pounds.

Amida, which means Infinite Light or Infinite Life, is one of the loftiest savior figures in Japanese Buddhism, and Amida faith is concerned primarily with the life to come (paradise). Amida is especially important to Japan’s Pure Land sects. The key practice for Amida devotees is simply to chant Amida’s name, “Namu Amida Butsu,” for Amida vowed that whoever calls his name with faith shall be reborn in the Western Pure Land. Rebirth in the Pure Land represents a “quick path” to enlightenment.

Poem by Rudyard Kipling

By Tophet-flare to Judgment Day,

Be gentle when the ‘heathen’ pray

To Buddha at Kamakura!

To him the Way, the Law, apart,

Whom Maya held beneath her heart,

Ananda’s Lord, the Bodhisat,

The Buddha of Kamakura.

For though he neither burns nor sees,

Nor hears ye thank your Deities,

Ye have not sinned with such as these,

His children at Kamakura.

Yet spare us still the Western joke

When joss-sticks turn to scented smoke

The little sins of little folk

That worship at Kamakura.

The grey-robed, gay-sashed butterflies

That flit beneath the Master’s eyes.

He is beyond the Mysteries

But loves them at Kamakura.

And whoso will, from Pride released,

Contemning neither creed nor priest,

May feel the Soul of all the East

About him at Kamakura.

Yea, every tale Ananda heard,

Of birth as fish or beast or bird,

While yet in lives the Master stirred,

The warm wind brings Kamakura.

Till drowsy eyelids seem to see

A-flower ‘neath her golden htee

The Shwe-Dagon flare easterly

From Burmah to Kamakura,

And down the loaded air there comes

The thunder of Thibetan drums,

And droned — “Om mane padme hums” —

A world’s-width from Kamakura.

Yet Brahmans rule Benares still,

Buddh-Gaya’s ruins pit the hill,

And beef-fed zealots threaten ill

To Buddha and Kamakura.

A tourist-show, a legend told,

A rusting bulk of bronze and gold,

So much, and scarce so much, ye hold

The meaning of Kamakura?

But when the morning prayer is prayed,

Think, ere ye pass to strife and trade,

Is God in human image made

No nearer than Kamakura?

— Rudyard Kipling

NOTES ON ABOVE KIPLING POEM

1892.

Great Buddha, but his poem upon the subject remains, in my opinion, one

of the most perfect evocations ever of ‘the Soul of all the East’.

Indeed, I can hardly read it without hearing Tibetan drums and scenting

joss sticks and seeing saffron-clad monks going about their morning

prayers…

It’s a profoundly religious poem, but no less universal or accessible

for that; in fact, I would call it, rather, a wonderful exaltation of

humanism and a call for gentleness and understanding. The philosophy

may not be ‘deep’, but it’s certainly very moving.

‘The Buddha at Kamakura’ should also serve as a rebuttal to those who

continue to view Kipling as a heavy-handed imperialist, a relic of

bygone colonial days. It’s true he sings the praises of the British

Empire (more specifically, of the soldiers and scribes who built that

Empire), but he is also more tolerant, more honourable, and above all,

more _universal_ than many of his contemporaries and latter-day critics.

And he had a rare gift of words – his verse, whether the Cockney slang

of Tommy Atkins or the pulsing rhythms of the Jungle Book or the archaic

patternings of today’s poem, is always vibrant and alive, and it sticks

in the memory.

On a personal note: I made the pilgrimage to the Daibutsu (the Great

Buddha) at Kamakura last weekend, and I must say it’s a truly

awe-inspiring spectacle. For one thing, it’s _big_ – it towers over the

hordes of tourists that infest the place. And it’s incredibly,

incredibly beautiful – the expression on the Buddha’s face is serene,

calm, compassionate, wise… ineffable. The statue is in the open (the

wooden structure that housed it was washed away in a tsunami, many

hundreds of years ago) (which in itself is a sobering thought), and it

sits in quiet repose through wind and rain, sun and shade. Sitting zazen

in the temple grounds really brought the power of today’s poem home to

me.

Thomas.

– Source : www.cs.rice.edu