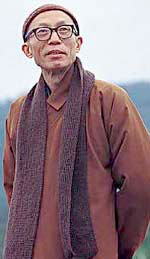

Master Sheng Yan

“Life is but a bus ride, death is only boarding another bus”

By YIP YOKE TENG, The Star, March 15, 2009

No grave marks his death, but Taiwanese monk Master Sheng Yan will never be forgotte by the millions of followers whose lives he touched

He died on Feb 3 at the age of 80, leaving behind some 200 books on Buddhism, and over a million followers worldwide, and a life story in which his commitment to education shines through.

On Feb 15, the Dharma Drum Mountain World Center for Buddhist Education in northern Taipei was filled with more than 30,000 followers from around the world, come to send off Sheng Yan’s ashes.

The ceremony was carried out in strict accordance to his will. The master, humble to the end, had said: “Do not write obituaries, do no present offerings, do not build a grave, stupa or monument, do not make statues, and do not collect my relics, if any.” Also, “Perform the ceremony not as a funeral, but as a Buddhist ritual”, and “all rituals must be carried out in a simple, frugal manner”.

Finally, respecting his environmental concerns, the master’s ashes were laid around several young trees in the centre’s eco-friendly memorial garden. The ceremony was no frills indeed: five holes were dug, his ashes divided between them, and the holes topped off with two scoops of earth each to hold a flower. Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou was among those who wielded a shovel.

Also, the simple process was witnessed by millions of Buddhists worldwide on TV. In Malaysia, a centre established by some of the master’s followers in Petaling Jaya was crowded yet orderly. The atmosphere was solemn but it was determinedly not sad. The master had advised against mourning because, after all, as he said, “Life is but a bus ride, death is only boarding another bus”.

At the end of the ceremony at the Dharma Drum Mountain, the master’s followers were invited to write a vow on a leaf-shaped note that was then hung on a man-made Bodhi tree. Those vows were the only “gifts” that the master had ever asked for from his followers, so that they, in order to fulfil their vows, would work hard to benefit all on earth.

To date, the tree has been laden with 25,000 vows, the last gifts for a man voted as one of Taiwan’s 50 most influential people in the last 400 years.

But it was not titles and accolades that made Master Sheng Yan so important, it was the way he respected, appreciated, and celebrated life that made his influence so far-reaching.

“He said as long as he was still breathing, he’d make sure that every minute spent was worthwhile,” says Rev Chang Hui, a Malaysian who was the first of Master Sheng Yan’s disciples.

“Every day, he woke up at 3am to write, and he slept only after 11pm. He taught us to always ask ourselves, what have I done today to benefit society? What have I done to deserve the bowl of rice I ate today?

“That was him, an industrious soul who could not waste even one minute. And he did what he pledged, even when he was critically ill, he did not stop reading and writing,” she says.

Always feeling that he had not done enough to propagate Buddhism, the master was always racing against time – yet, he never lost his cool.

“I first met the master in 2001, my first impression was, ‘How could he be so relaxed?’ says Lim Tiong Hong, Dharma Drum Mountain’s Malaysian coordinator. “I had read about him and I could guess how many things he would have had on his plate. He was even recuperating from a serious illness then.

“I just could not fathom how he could still hold his calm and even chat with me casually, just like a family member,” Lim says, the wonder still evident in his voice.

Born on a farm near Shanghai in early l931, Sheng Yan’s childhood was riddled with illness, floods, droughts, and wars but none of it diluted his innate compassion.

Long before any formal studies in Buddhism, he was already driven to share, as his encounter with his very first comb of bananas shows: he couldn’t take a second bite of the fruit because he wanted his classmates to also experience its “wondrous taste”.

When he was barely 13, he asked to join a monastery in the Wolf Hills, and soon discovered the power of Buddhist dharma (knowledge) in freeing people from suffering. He vowed to spread it to as many people as possible so that they, too, could attain the happiness he had.

But his studies were interrupted when, in 1949, as China plunged into revolutionary chaos, he was conscripted into the Nationalist army – but still he read voraciously on Buddhism. His dream of receiving his tonsure finally came true after 10 years as an information officer.

Though having only completed the fourth grade formally, such was his commitment to studying and writing about Buddhism that Sheng Yan was admitted to the master’s programme in Buddhist Studies at Japan’s Rissho University on the strength of his published works alone. Subsequently, he became the first Chinese monk to obtain a PhD.

With that, the tall and thin monk began trotting around the globe to teach Chan (Zen), the soul of Chinese Buddhism, in a way that modern generations could relate to.

“To me, his approach, interpretation, and application of the dharma was his greatest legacy,” Lim says.

“Through him, millions of people finally realised how close Chan is to them and how Chan can be applied in their workaday lives to bring tranquillity to their souls,” he explains.

In 1978, the Venerable Sheng Yan succeeded his teacher as the abbot of Nung Chan Monastery and head of the Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Culture. Students and devotees were increasing in number as word of Sheng Yan’s teachings spread, and soon, there was a dire need for more space.

After eight years of searching, Sheng Yan finally found the right place in Jinshan township, Taipei county, and named it Dharma Drum Mountain. It soon became a place where people from all over the world came to learn Buddhism in a tranquil and academic environment.

To the monks and nuns who studied under him, Sheng Yan was a no-nonsense teacher devoted to cultivating religious scholars who could explore and expand on Buddhism.

“The example he set was unmatched,” says Rev Chang Hui, recalling how the master’s selflessness propelled her to choose a monastic life. “I was touched when he said Buddhism graduates were the world’s assets. Those words opened my eyes, that one’s heart could be that big, and one’s love could be so great,” she says.

She explains how the master launched a Renaissance of sorts, as he set out to debunk wrong perceptions of Buddhism. This entailed an amazing effort to translate the immense number of sophisticated ancient sutras (an aphorism or a series of aphorisms) into a set of interpretations and applications that could be easily grasped by modern people.

“Not many can write like Master Sheng Yan – his works can be understood by primary students yet are also appreciated and applauded by academicians,” says Rev Chang Hui.

Master Sheng Yan was a huge influence on many Malaysian Chinese Buddhists, say Lim, explaining that, “Many Chinese thought that they were Buddhists but, in fact, they were only practising Chinese customs, praying to gods for health, safety, and good fortune – even my family was like that.

“The real Buddhist teachings are significantly more widespread now through the talks, books, and meditation sessions the master conducted or through the efforts of the Malaysian Buddhist Association led by chairman Venerable Chi Chern, who was under Master Sheng Yan’s tutelage for more than 20 years.”

Thanks to such efforts, “In Malaysia, Buddhism is now widely accepted as a philosophy, a way of life,” Lim says.

The Dharma Drum Mountain’s Malaysian information centre can be reached at 03-7960 0841 or 03-7960 4341. For details, visit

www.ddm.org.tw or ddm.org.my.

Source : The Star