Korea has a unique cultural heritage listing system for recognizing intangible skills that have been passed on through the generations. Among these is “seungmu” or monk’s dance, which is one of the most well-known folk dances. It was designated as Korea’s Important Intangible Cultural Asset No. 27 in 1968.

Korea has a unique cultural heritage listing system for recognizing intangible skills that have been passed on through the generations. Among these is “seungmu” or monk’s dance, which is one of the most well-known folk dances. It was designated as Korea’s Important Intangible Cultural Asset No. 27 in 1968.

The dance, as its name suggests, comes from the Buddhist tradition. Its origins can be traced back to about 500 years, and to this day it has been passed on as a dance performed during Buddhist ceremonies, as a form of physical expression of making an offering to Buddha. However, the seungmu that one often encounters these days are staged works with strong theatrical elements that stand as an artwork that strives for universal, rather than religious ideals. It should thus be considered more a folk dance rather than a Buddhist ritual.

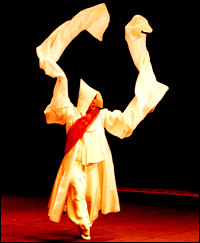

It draws beautiful spatial designs by using the long sleeves of the costume coupled with characteristics of the Korean traditional dance such as harmony of motionlessness, dynamism and subtlety. It has evolved throughout the years in Korea and has been refined to become a theatrical dance form leaving its religious origin behind.

Popular legend has it that Hwang Jin-i, a “gisaeng” or courtesan and famous poet, dancer and musician of the Joseon Kingdom (1392-1910), was the first to adapt the Buddhist dance to artistic ends ― she added a sensual twist to the movements to seduce the famous Buddhist priest Jijokseonsa, who was so entranced by her beauty that he gave up his priesthood.

Nevertheless, the spiritual ideals inspired by Buddhism remain intact. Even before looking into the dance movements and the meanings behind them, it doesn’t take more than a single glance at a seungmu dancer to discern the Buddhist roots. The costume ― conical hat, red sash and all ― look just like a monk’s wardrobe.

Moreover, it is about expressing a spiritual ideal.

“It’s a sacred dance, a meeting point between humans and heaven,” Jung Je-man, a National Living Treasure or master of seungmu, told The Korea Times in his Cheongdam-dong studio last week.

“The dance must be executed with seriousness, with each movement rendered with the utmost care and all of your heart,” he said. Seungmu is ultimately a form of “seon”or meditation.

The 62-year-old artist, along with Lee Ae-ju, is inheritor of the Han Seong-jun/Han Young-suk branch of seungmu while Yi Mae-bang is the protege of the Lee Dae-jo branch of the dance.

Yi, 84, who, in addition to dance, is trained in Korean traditional music including “pansori” (Korean opera) and “gayageum” (12-string zither), said that the sacred aspect of seungmu is reflected in the music itself. Most of the other traditional dances are geared toward entertainment and teasing the crowd, and can be performed to the beats of a drum or the like. Seungmu, however, requires a full “samhyeon yukgak” or six-part band ― two “piri”(Korean flute), “haegeum” (two-string fiddle), “daegeum” (horizontal bamboo flute), “janggo” (hourglass-shaped drum) and “buk” (drum).

Jung recalled the days of learning seungmu from his late master Han Young-suk, who inherited the mastery of seungmu from her grandfather, Han Seong-jun. “My teacher (Han Young-suk) was a very devout Buddhist. She frequented the temple very often. Seungmu is a form of seon ― you try to purge yourself of your sins and worries through dance,” he said.

Jung himself, however, is actually Catholic. “I’m Catholic; when I was young I even thought of becoming a priest. But regardless of my faith I find the idea of practicing seon through dance very beautiful.” In 2007, he produced a large-scale work “108 Seungmu” in which 108 dancers, including himself, showcased seungmu in unison in the outdoor square of Olympic Park, in Seoul. The 108 refers to the Buddhist practice of doing 108 bows, based on the belief that man goes through 108 periods of anguish in life.

In the famous poem “Seungmu,” the poet Cho Ji-hoon writes, “One may be harassed by worldly affairs but suffering is the twinkle of a star.”

Seungmu consists of five acts. The opening act, “yeombul dongjak” or Buddhist prayer motion, perhaps best reflects the Buddhist influence. The dancer usually starts off lying face down on the floor, and following the beats of “moktak”or wooden percussion instruments used for chanting by Buddhist monks, the dancer twists his torso and rises up, as if finishing up a deep bow to Buddha.

“Here the dancer is facing the center of the stage, which implies that there is a subject, which in this case is a supernatural force like Buddha or God,” said Jung.

A change in dynamics takes place in the next two acts, “dodeuri” and “taryeong.” The calm, quiet ambiance of the first act takes on a more vibrant atmosphere as the dancer engages in rhythmic shoulder movements and footwork. Yet the dance does not lose its solemnity.

The action climaxes however in the “beopgo” act, featuring the namesake Dharma drum. This part is a most obvious reference to the dance’s Buddhist roots since the beopgo is one of the four Buddhist instruments along with “beomjong” (temple bell), “mokeo” (wooden fish) and “unpan” (cloud gong) that are found in Buddhist pavilions. “The dancer starts beating the drum, which symbolizes an act of redemption and inspires a feeling of catharsis,” said Jung. The dance then tapers off and ends on a tranquil note.

“I believe seungmu transcends the boundaries set by religious or cultural traditions. I think the overall flow of the acts, as it ascends to a climax and then regains a sense of calm, is a lot like life ― you start out as a helpless child then grow into an energetic youth, and then things slow down as you age,” he said.

– By Lee Hyo-won, The Korea Times

– Source: www.buddhistchannel.tv