02.08.2010

Three short and intimate films about William Segal, a painter and spiritual teacher, that Ken Burns and his colleagues made from 1992 to 2000 were mostly meant to be seen within Mr. Segal’s personal and professional circles.

But thanks to films like “Baseball” and “The War,” Mr. Burns’s fan base has kept growing. Each new documentary he makes draws millions of viewers to public television. And the Segal films, which have occasionally been screened in museums and were released without much fanfare in 2002 in a DVD trilogy called “Seeing, Searching, Being,” have become something of an underground commodity for devotees of Mr. Segal’s approach to self-realization.

Now more people will get to take a look. PBS, which has exclusive rights to Mr. Burns’s work, is bringing two of the three films, “William Segal” and “In the Marketplace,” to television for the first time, for stations to use during their August and September pledge drives. (Viewers should check local listings for broadcast dates.)

The third film, “Vézelay,” which is more overtly spiritual than the other two, will be available with the others on a DVD (a reissue of the out-of-print 2002 version) that will be given as a premium to viewers who make donations of a certain amount. In addition the Rubin Museum of Art in Manhattan plans to screen “William Segal” and “Vézelay” on Nov. 17.

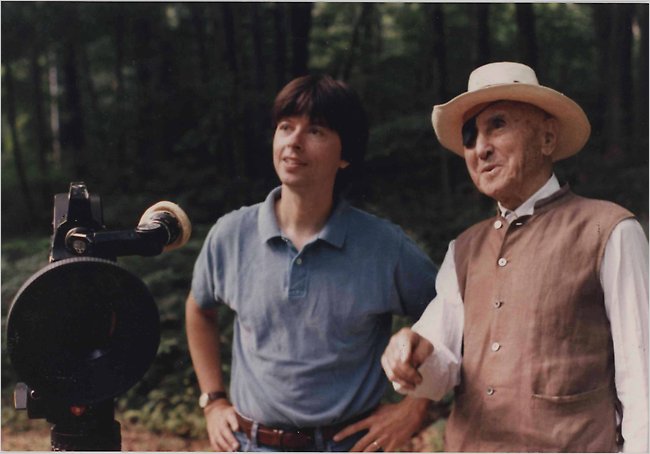

Mr. Burns first met Mr. Segal in the mid-1970s in a drawing workshop in the basement of a church in Dorchester, Mass. That first meeting was a “superficially innocuous interchange,” Mr. Burns said in a recent interview, but the striking Mr. Segal, almost bald and wearing a black eye patch after a 1971 car accident, made a strong impression. “He had a kind of vitality that — I had never met anyone like that — that kind of rearranged my molecules,” Mr. Burns said.

Mr. Segal, who died in 2000 at 95, was a self-made man from Macon, Ga. A star athlete who attended New York University on an athletic scholarship, he was a young painter in New York when he ventured into magazine publishing. His publications included the garment industry trade magazine American Fabrics and the elegant, short-lived men’s fashion title Gentry — and they made him a millionaire.

He continued to paint, including a lifelong series of self-portraits that were part of his quest for understanding as he immersed himself in Eastern religions and spirituality. He was a student of Daisetz Suzuki, the foremost exponent of Japanese Zen Buddhism in the West, and of the Greco-Armenian mystic and philosopher Gurdjieff. Mr. Segal was co-chairman of the Gurdjieff Foundation when he died.

Mr. Burns and Mr. Segal kept in casual touch after that drawing class. Mr. Burns recalled inviting Mr. Segal to view a rough cut of his 1981 film, “Brooklyn Bridge,” and at one point he bought a Segal self-portrait at an exhibition.

The friendship solidified in 1992. In a recent interview in her apartment on the Upper East Side, Marielle Bancou-Segal, an artist and designer who was Mr. Segal’s second wife, described Mr. Segal’s connection to the filmmaker. “The relationship he had with Ken was beautiful,” she said, “like a father and son should be.”

Mr. Segal was preparing an exhibition of his artwork in Tokyo when the organizers asked for a short film that would explain him to the Japanese. Not knowing any other filmmakers, Ms. Bancou-Segal suggested calling Mr. Burns, whose 1990 documentary, “The Civil War,” had made him famous. It was August; the Segal film was needed for October, Ms. Bancou-Segal recalled, laughing at her own naïveté.

Even so, Mr. Burns agreed to the quick turnaround for what he now calls “a labor of love,” and with colleagues who included Buddy Squires and Roger Sherman spent several days at the Segals’ farm in Chester, N.J., filming Mr. Segal talking about his philosophy of painting and seeing.

That 13-minute film, “William Segal,” was followed by the 30-minute “Vézelay,” shot in 1995. It grew out of a vacation trip. (The Segals also had a home in Paris.) Filled with contemplative scenes from in and around the Basilica of St. Mary Magdalene in the French town of Vézelay, it was filmed as sunlight filtered through the windows at the summer solstice, and it includes footage from a meditation session led by Mr. Segal in the crypt and his commentary on humanity’s search for identity.

In 1999 Mr. Burns returned with Mr. Segal to Paris as he prepared an exhibition and finished a book of lithographs. The resulting 30-minute film, “In the Marketplace,” was inspired by Zen Buddhism’s 10 Oxherding Pictures, which describe a cycle of life and search for enlightenment that ends with the old man in the marketplace, “free of all attachments, and you can go into the marketplace literally as a child would, full of that innocent wonder,” Mr. Burns said. He finished the film days after Mr. Segal’s death.

The films are unlike Mr. Burns’s better-known work. They emphasize long periods of silence, there are no historical documents, there is no narrator; for viewers unfamiliar with Mr. Segal, Mr. Burns has recorded a biographical introduction. Most of Mr. Burns’s films emerge from hour upon hour of footage, but here the team put most of what was filmed on the screen.

Still, the process “was actually no different than any other film,” he said. “But in this case we weren’t bringing any element of a narrative overlay.”

“It didn’t need it,” he added. “These were little films that could tell themselves.”

Mr. Burns called the filmmaking “a daisy chain.”

“We just connected stuff, but in that simplicity something comes through,” he said. “What comes through is that he comes through. That’s all we ever wanted, was to not interpose ourselves between Mr. Segal and what he had to say.”

Ms. Bancou-Segal agreed: “It is not so much the facts as the impression.” Of Mr. Burns she added: “He should do more films on people alive. I told him that.”

Source: The New York Times