The Mahayana schools of Buddhism appeared sometime around the first century BCE. They include every form of Buddhism that is not Theravada (such as Zen, Nichiren, Pure Land, Shin, and Tantric Buddhism to give a small set of examples) and are currently predominantly present in central Asia. The Mahayana schools began when new scriptures purporting to be the words of Siddhartha began circulating. These works are today recognized as not being spoken by Siddhartha, but by later Buddhists. Despite this, Mahayana Buddhists around the world hold that since what these scriptures, or Sutras, say rings true, it does not matter who originally wrote or said them and continue to study, recite and follow what they contain.

The Mahayana schools of Buddhism appeared sometime around the first century BCE. They include every form of Buddhism that is not Theravada (such as Zen, Nichiren, Pure Land, Shin, and Tantric Buddhism to give a small set of examples) and are currently predominantly present in central Asia. The Mahayana schools began when new scriptures purporting to be the words of Siddhartha began circulating. These works are today recognized as not being spoken by Siddhartha, but by later Buddhists. Despite this, Mahayana Buddhists around the world hold that since what these scriptures, or Sutras, say rings true, it does not matter who originally wrote or said them and continue to study, recite and follow what they contain.

The major difference between the Sutras and the earlier Suttas, is the concept of the Bodhisattva. The Sutras hold that, out of compassion, some who are on the verge of enlightenment hold off on becoming full-fledged Buddhas because the rest of the life on Earth is still suffering. These people, who are known as Bodhisattvas, vow to not become enlightened until every sentient being can become enlightened with them. The Bodhisattvas are treated as spiritually powerful entities, who constantly reincarnate and guide their fellow humans towards enlightenment. The Sutras also describe Buddhas other than Siddhartha. These other Buddhas are enlightened men and women from the Earth’s past, or from other planes of existence or other planets. These new Buddhas, and Siddhartha himself, are also elevated to a god-like status and held up as beings to pray to and worship.

The addition of Bodhisattvas to Buddhist thought gave power back to the laity. Though many Bodhisattvas were monks in their previous lives, others reached their state while still being “house-holders”, men and women who lived normal lives and had families. Enlightenment was once again open to everyone. Furthermore, the ideal of holding off full enlightenment until the rest of life was ready to enter that state with you invigorated practitioners into a sense of compassion that the earlier schools only wrote of as a nice thing to try to do. The pre-Mahayana schools were given their “lesser” status and some of the Sutras had Siddhartha disparaging the Hinayana schools as being for the “weak minded” and the “selfish”.

Mahayana brought a good deal of changes to Buddhism, some good and some less so. The new, god-like Bodhisattvas and Buddhas caused many to decide that this world was not worth worrying about at all since if they prayed hard enough, they would be reborn in paradises. In particular, Pure Land Buddhism, historically and currently one of the most popular Buddhist sects throughout Asia, focused on the Buddha Amitabha, a Buddha from the Larger Sutra of Immeasurable Life who created a heavenly dimension known as the Pure Land which a practitioner is guaranteed entry in to in their next lifetime, so long as they have faith in Amitabha. This had the two effects: it allowed members of society who previously could not be Buddhists in good standing, such as soldiers, prostitutes, and butchers a sect which they could belong to, and at the same time caused many to decide that it didn’t matter how they acted when they were alive since Amitabha was going to save them regardless (famously, a group of Pure Land Buddhists became assassins in medieval China, setting out to prove the greatness of Amitabha by making their livings as killers and still hoping to enter the Pure Land).

This focus on the supernatural moved Buddhism away from its roots and, over time, lay people once again began for the most part to simply pray and to give donations to wandering monks. Some sects, such as Zen Buddhism, tried to move back to a more phenomenological ground.

Zen was founded around 520 CE by Bodhidharma, a monk who traveled from India to China to teach a stripped down version of Buddhism. To Bodhidharma, praying to Bodhisattvas and giving donations to monks did not result in enlightenment. Meditating and living a good life were the paths he preached. Helping the poor was not something to be done so that one would be reborn in a rich family, it was something one should do because then the poor were helped and this made the world a little better.

Hui-Neng, the sixth patriarch of Zen (638-713 CE), came from a less-than-ideal background. He was ethnically Lao, a minority in ancient China that was considered intellectually inferior to the predominant Han ethnicity. In addition, his father had been banished from the Imperial court, and Hui-Neng was raised in a rural mountain town, cutting firewood for a living and never learning how to read or write. In the one document based on his teachings (and the one Sutra that was never claimed to have been spoken by Siddhartha), Hui-Neng tells an audience this, and how despite being an illiterate from an ethnicity that most Chinese citizens looked down on, he achieved enlightenment because “Men know North and South, but the Dharma (teachings) does not.” He also explains that, if people want, this world can be the Pure Land and, if it was, would be a more reachable one than that promised by Amitabha (“Ordinary, ignorant people, not realizing their own essential nature, do not recognize the Pure Land in their own bodies.”). Despite all this, Zen was primarily practiced by monastics historically, and was once again more concerned with renouncing the world rather than attempting to improve it.

It is not until the beginning of the 20th century that sects of Buddhism become chiefly concerned with social activism. An early step in this direction was the work of a Zen monk in China named Taixu or “Great Emptiness” (birth name: L? Pèilín ) Taixu wrote about what he called “Humanistic Buddhism”, which he contrasted with Buddhism that was primarily concerned with ghosts, reincarnation, and the supernatural. One of his students, Hsing Yun (“Nebula”) has written many pamphlets on Humanistic Buddhism and still teaches about it to this day.

As Buddhism moved in to the 20th century, it adapted fairly well to the advances that history brought. Though Japanese Buddhists supported the Axis powers in World War II, they have since apologized publicly whenever the issue is brought up and have made few attempts to hide what happened. Buddhist leaders such as the Dalai Lama and Gudo Nishijima (the head of the largest Zen monastery in Japan) fully support advances in physics and biology, admitting when these sciences contradict their scriptures that the scientists are in all likelihood right, and writing extensively on the connections between science and Buddhism. Socially conscious Buddhism, or “Engaged Buddhism” is a byproduct of this modernism and the Humanistic Buddhism of Taixu.

Engaged Buddhism, also known as Socially Engaged Buddhism, works to apply the pacifism, equity, compassion, and focus on community that Buddhism is clasically associated with on a global scale. Some argue that it is Buddhism mixed with the Protestant Christian work ethic, though others feel that it is simply the natural evolution of what Siddhartha Gautama taught 2,500 years ago.

Thich Nhat Hanh (“Being in Touch With Here and Now”), a Zen Monk from Viet Nam, has spent most of his life working towards teaching pacifism throughout the world, and was nominated by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1967. He founded a separate sect of Buddhism, the Order of Interbeing, in the 1960s which is devoted to social equity, environmental protection, and helping the victims of war. He even rewrote the Buddhist Precepts, the closest Buddhists have to a “Ten Commandments”, to be more in touch with the issues we are presented with in the modern world.

Noah Levine is another modern Buddhist who has worked in the general school of Engaged Buddhism. He is a former crack addict and juvenile delinquent who now is the primary spiritual teacher of the “Dharma Punx” sangha. Levine, through his books Dharma Punx and Against the Stream: A Buddhist Manual for Spiritual Revolutionaries and through his work traveling to prisons, juvenile halls, and Buddhist temples, has tried to introduce a form of Buddhism that he hopes can reach at-risk youth, a position that someday should play a part in technoprogressivist philosophy. His friend, and another recovering addict, Vinnie Ferarro, heads the Mind Body Awareness Project which the two founded together.

Many other Buddhist teachers, such as Bernie Glassman, Bhikkhu Bodhi, Jack Kornfield, Sheng Yen, and James Ford work in the purview of Engaged Buddhism. In many ways, it is similar to the Bodhisattva ideal of the early Mahayana sutras, men and women working to bring the world closer to enlightenment with each passing day. The idea of “transcending” what it is to be human is at the forefront transhumanist philosophy. As George Dvorsky also points out;

“[Buddhism] is an epistemological philosophy and an intrapersonal approach to perception, self-awareness and self-regulation. It’s an aesthetic. It’s a non-anthropocentric ethical viewpoint that places an emphasis on meaningful, compassionate and genuine relationships. It’s a type of Humanism. It encourages meditation and a mindful approach to living. It’s a worldview and methodology that promotes skepticism, rationality, empiricism and even non-conformity. It is the practical acknowledgment of the unavoidable perceptual subjectivity that is part of the human condition. It is the recognition that the mind matters and that conscious awareness can and should be optimized.”

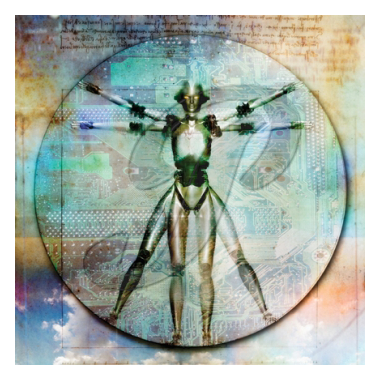

Since its inception Buddhism has changed a great deal. However, throughout its history, it has always been concerned with improving the lives of those it encounters. Much of the time, it did not even require one to convert to Buddhism for Buddhists to attempt to help, and its strong lack of dogmatism has helped it adapt to the needs of modern society. Whether the coming years will see Buddhists work more towards establishing a Pure Land here and now, or whether they will see a retreat once again to monasteries and to attempting to avoid the world’s problems, it is clear that the history of social activism in Buddhism is a long and checkered one, and a history which will have new chapters added to it, for example its impact on transhumanism as the “religion” continues to influence sentient beings whether they are human or cyborg.

Click here to read the beginning of this article

Source: ieet.org