The blind side of Bhutanese Buddhism

Going around in circles

Is our religious practice restricted to ritual?

By Gyalsten K Dorji, Kuensel Online, March 14, 2009

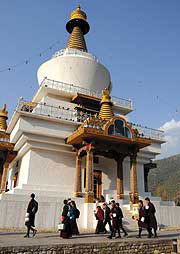

Timphu, Bhutan — ‘Why do you practice Buddhism? “To fulfill my desires, get a good job and earn more money,” said a class 9 Yangchenphug student, who had just completed his daily routine of circumambulating the Memorial Chorten in Thimphu.

Jigme Namgyel, a class 12 student of the same school, said, “Because my parents are Buddhist.”

Jigme Namgyel, a class 12 student of the same school, said, “Because my parents are Buddhist.”

Karma Phuntsho, another student, said, “Because I was born in Bhutan.”

Bhutan may be the last bastion of Mahayana Buddhism, of a predominantly Buddhist society and culture, but Bhutanese youth are growing up unaware of the fundamental principles of the religion they practise, says Buddhist scholar Dr Karma Phuntsho.

Dr Karma Phuntsho, who is also the president of the Loden Foundation in Bhutan, an organisation that supports learning and education of culture and religion, attributed this gap to a “major linguistic gap between the custodians of Buddhism and our young generation”.

“The risk is, without a significant and logical understanding of Buddhism, our culture and traditions could be lost,” said Dr Karma Phuntsho.

Dr Karma Phuntsho said that the practice of Buddhism in Bhutan had not changed from when it was first institutionalised in the 17th century by Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyel. “You see the most learned and most popular lamas go to the West and teach proper Buddhism to their students but, when they come back to Bhutan, they just touch the head of their devotees.”

“It’s the fault of spiritual teachers, who haven’t been able to present Buddhism in the context of the times,” said Phuntsho Rabten, one of the founders of the Deer Park Thimphu Centre, an organisation that promotes exploring Buddhism through art and contemplation.

Besides the monastic institutions in the country, no others are responsible for providing in-depth philosophical explanations about Buddhism. As a result, Buddhism has become more of an external practice rather than an internal one among not only students but the entire society as well, he said. “Nowadays people actually see Buddhism as a spiritual insurance company, which is actually not the Buddhist path,” he said.

Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, a popular spiritual teacher in Bhutan and abroad, in an email interview, attributed this problem to a culture of unquestioning respect and reverence. “Ironically, our very own tradition, culture, customs, or, if you like, our so-called ‘driglam namzha’, are actually also culprits,” said Khyentse Rinpoche. He said that, although he would like to go out and meet with the youth on the streets, or in bars and restaurants, and talk with them informally, he was hesitant to do so. “Nobody would dare sit next to me and talk freely about their lives,” he said. “I’m sure that people would be shocked.”

Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche believed traditional language was not the only obstacle but also the representations, symbols and rituals used to communicate with the community. He said educated Bhutanese youth were not able to comprehend such symbols. He pointed out that even younger monks could not easily comprehend Buddhist texts, such as the Kangyur or Tengyur, which are written in Choekyed, a classical Buddhist language.

Lam Shenphen Zangpo, a visiting Buddhist monk from the UK, also observed that Bhutanese youth were more ritualistic in their practice of Buddhism. “Some are just going around the chorten.” But he did not think this was a contradiction of the fundamental principles of Buddhism. However, he did think both the traditional and modern approaches like Deer Park-Thimphu, which organises discussions on Buddhism for youth, was essential in the exploration of Buddhism.

What could be done

To close the gap, Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche said, “The government and individuals should also really try to use modern media – modern language – to bring in the Buddha’s teachings of compassion, love, kindness and interdependence. I think it’s very important that we don’t get caught up with needing to use only Buddhist terms and Buddhist symbols.”

Dr Karma Phuntsho said both sides were at fault – youth for not learning and reading Choekyed and Dzongkha, and the monks, for not learning English to transmit their messages to a society brought up in an educational system biased towards English. Asked why students should be expected to learn Choekyed and Dzongkha to understand the basic principles of Buddhism, Karma Phuntsho, who also translates Buddhist texts into English, said, “Language plays a major role in what the message should sound like, the puns and poems wouldn’t work, a lot of the effectiveness that’s embedded in language, will be lost.”

But, at the same time, he also thought the way Buddhism was practised in Bhutan could be more informal. He said, “Religious ceremonies, instead of just being a formal unquestionable practice, should open up to the huge number of educated young people starting to question.” He said, “Questioning is a very important part of Buddhism. The Buddha built his system on the basis of questioning.”

Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche plans to open a gathering place in Thimphu, where the youth can come and express themselves through music, poetry, film, dance and to discuss Buddhism and other issues. “I think it would be a real shame (if nothing is done) to lose this already existing infrastructure (Buddhist culture), that could help us to enrich ourselves spiritually, enrich ourselves with the awareness, or the wisdom, that is so much needed during this age.”

– Source Kuensel online