Sep 29, 2009

Hanoi — Four years ago the Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh, a monk who popularised Buddhism in the West, was invited by the Vietnamese government to return home after 39 years in exile.

But four years on, there are signs that the authorities’ new-found tolerance is waning.

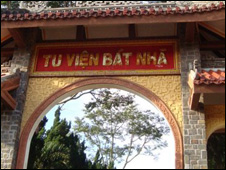

Followers of Thich Nhat Hanh say they have been forced out of a monastery by police and angry crowds who ransacked the building over the weekend.

Reports say about 150 monks were evicted from the Bat Nha monastery and more than 200 nuns left on their own on Monday.

And Catholics in Vietnam have been embroiled in a two-year dispute with the government, holding mass demonstrations to demand that the authorities return land they say belongs to the Church.

Relaxed approach

The government believes religion should be a private matter but had begun to ease its grip on religious freedom largely for economic reasons.

Some analysts say that before joining the World Trade Organisation in 2007, Hanoi was under pressure from the US and European governments to grant people greater religious freedom.

So the government took a more relaxed approach.

Pilgrimages by party leaders to temples and shrines of famous local deities used to be very low key, but they became acceptable and were featured regularly in the media.

Monks from the pro-government Vietnam Buddhist Sangha were often invited to bless ministerial buildings or chant prayers at military funerals.

But with Vietnam now in the WTO and removed from a US State Department religion blacklist, some analysts believe the government has reverted to its old ways.

The diplomatic charm offensive worked, the thinking goes, and there are fears that any further relaxation would potentially threaten the party’s monopoly on power.

For example, the government says Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh’s followers were asked to leave by the monastery’s abbot – they describe the standoff as a conflict between two Buddhist factions.

But critics say the clampdown began when Thich Nhat Hanh urged the government to stop controlling religion and called for the religious police to be disbanded.

Organising power

There is also the land dispute between the Catholic church and the government.

Despite many high-profile meetings, the Vatican and the government have failed to reach agreement and Hanoi shows little sign of backing down.

During a recent visit to Budapest, Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung firmly defended Hanoi’s policy, asserting that “the Vatican has no properties in Vietnam”.

It seems unlikely that a consensus will be reached when the President Nguyen Minh Triet visits the Vatican later this year.

Religious belief is on the rise in Vietnam

Efforts to normalise relations with the Vatican have been further hampered because some Catholic activists have been jailed, and there have been confrontations between demonstrators and security forces.

State media have played down the growing tensions but the international Catholic media have published videos and news reports of the ongoing protests and tensions.

Father Huynh Cong Minh from the Archdiocese of Saigon says that ”like it or not, the Catholics in the world are organised and that is what the communist government fears the most.”

Speaking to the BBC Vietnamese service he rejected accusations that the Catholic Church was acting “against the government”.

However, he did say the Church should have a say in social issues and should speak out against corruption.

Nguyen Hong Duong, a pro-government former head of Hanoi’s Institute of Religious Studies told the BBC that “some Catholic priests have tried to turn civil disputes into a religious issue and this must stop”.

Ideological instinct

Despite the official unease, many people, and especially young professionals are increasingly turning to religion.

Millions of pilgrims now travel annually across the country to distant shrines of local deities as well as Buddhist temples and Christian churches.

As one Hanoi resident explains: “On television, we see how football players like Ronaldo make the Christian sign of the cross. So religion cannot be such a bad thing.”

Also worrying for a government which does not want religion infringing on politics, is the fact that many of the country’s most prominent dissidents, human rights activists and pro-democracy lawyers are Christians.

In the face of these latest religious challenges, and with the next Communist Party Congress being held in just over a year, some analysts believe that is why the old ideological instinct to exercise control might have resurfaced.

By Nguyen Giang

Source : BBC Vietnamese service