KARMA, REBIRTH, AND MENTAL CAUSATION

By Christian Coseru

PART 2

Christian Coseru

Department of Philosophy

College of Charleston

Read in first

– Part 1

It is important to understand that mind as currently understood in the scientific

literature is, in Thompson’s own words, “an abstraction from, and hence

presupposes, our empathic cognition of each other.” Operating with a model of

the mind that departs from the standard cognitivist-computational model, Varela

and Thompson view mental processes as “embodied in the sensorimotor activity

of the organism and embedded in the environment.”14 This is what Varela and

Thompson refer to as the embodied and enactive model of the mind, a model

relying on the following three principles:

- “Embodiment. The mind is not located in the head, but is embodied in the

whole organism embedded in its environment. - Emergence. Embodied cognition is constituted by emergent and selforganized

processes that span and interconnect the brain, the body, and

the environment. - Self–Other Co-Determination. In social creatures, embodied cognition

emerges from the dynamic co-determination of self and other.”15

An embodied and embedded consciousness in which the patterns of codetermination

are operative at both ends raises the issue of causal powers from

the direction of conscious will. However, whether consciousness is regarded as

having causal powers or not, the most difficult problem remains that of

adequately specifying the criteria under which brain states can be interpreted as

aspects of cognitive processing. Apart from the difficulties inherent in any attempt

to close the explanatory gap, whether from the direction of experience or from

that of neuroscience, a naturalized account of consciousness and its pragmatic

efficacy is also confronted with what the French philosopher Paul Ricoeur, quite

aptly, terms the “semantic amalgamation”.16 Ricoeur is inclined to adopt what he

calls a “semantic dualism,” which plays a useful heuristic function. He further

observes that “[t]he tendency to slip from a dualism of discourses to a dualism of

substances is encouraged by the fact that each field of study tends to define itself

in terms of what may be called a final referent.”17 This referent, which for

philosophers is the mind and for neuroscientists is the brain, is also in some way

defined “as the field itself is defined.” Ricoeur warns thus of the risks of collapsing

these two referents:

- It is therefore necessary to refrain from transforming a dualism of referents into a

dualism of substances. Prohibiting this elision of the semantic and the ontological

has the consequence that, on the phenomenological plane … the term mental is not equivalent to term immaterial in the sense of something noncorporeal. Quite

the opposite. Mental experience implies the corporeal, but in a sense that is

irreducible to the objective bodies studied by the natural sciences.18

I draw attention to this “semantic amalgamation” partly as a criticism of the usual

“the brain thinks” or the “amygdala feels” modes of discourse currently in use in

neuroscientific literature, and partly to emphasize the inherently linguistic nature

of knowledge representation in which both phenomenological and neuroscientific

accounts of cognition find their expression.

This is evident in the fact that the body, as the medium where lived experience

takes place, is part of the continuum of life, of what Husserl called the life-world

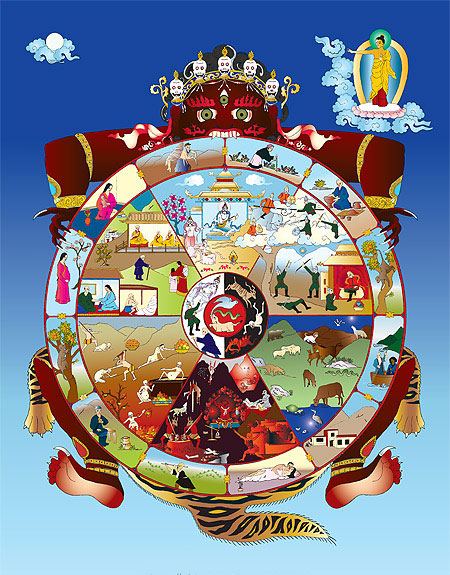

(Lebenswelt). In the Buddhist context, the problem of embodiment finds

expression in discussions concerning karma and rebirth. More specifically, for the

Buddhist philosophers the problem of embodiment is framed by the dispute over

the relationship between cognition and the body. This issue is addressed in

detail, for instance, in Dharmakīrti’s refutation of materialism in his dispute with

the Cārvāka philosopher Kambalāśvatara, where he defends a thesis that is

somewhat contrary to modern views of biological determinism:

- Nor are the senses, or the body together with the senses, the cause of cognition,

for] even when every single one of the senses is impaired, the mental cognition is

not impaired. But when the mental cognition is impaired, their (i.e., the senses’)

impairment is observed.19

The gist of Dharmakīrti’s argument here is that an impairment caused to any of

the senses does not impact on the overall cognitive capacities of an individual but

only on his ability to communicate his inner states via that sensory modality.

However, the reverse is not true, as any fundamental impairment to one’s mental

capacity renders the senses useless. This corresponds approximately to what

modern psychology calls agnosia, a state in which one is unable to recognize

and interpret objects, people, sounds, and smells, despite the fact that the

primary sense organs are intact. Ostensibly, Dharmakīrti’s argument in favor of

taking rebirth as axiomatic in the discussion of cognition (expanded at great

length by Śāntarakṣita and Kamalaśīla in their own refutation of materialism in

the Tattvasaṃgraha) is simply an extension of his theoretical commitment to the

Yogācāra psychology and, indirectly, to the Buddhist principle of the momentary

nature of all phenomena. That this focus on cognition as a lived experience and

on the phenomenology of the present moment finds a distant echo in Husserl’s

phenomenology comes as no surprise, given the common premise on which both

Yogācāra and Phenomenology operate, namely the primacy of the moment as given in direct experience. This convergence in clearly illustrated by Dan

Lusthaus:

- We note as a point of interest that for both Husserl and Yogācāra the present

moment alone was real, and yet the present is never anything other than an

embodied history. Phenomenology reached history through the moment by an

innovative method of reflection on and description of that moment. Conversely,

Yogācāra arose out of a history, namely, Buddhist tradition that carried a karmic

theory of historical embodiment. The primacy of the moment was bequeathed to

them through that history; and they reinterpreted that history in the light of an

epistemology that, like Husserl, scrutinizes the structure of a moment of cognition

in order to recover its context and horizons. For both Husserl and Yogācāra

understanding involves a leap from the present as mere presence to embodied

history, to the uncovering and reworking of habitual sedimentations — and in the

case of Yogācāra, the ultimate elimination of habit (karma) altogether.20

Developments in the sciences of cognition in the past few decades have greatly

enhanced our understanding of the adaptive nature of human cognitive functions.

We now know for instance that the operation of our perceptual systems is

functional only within a certain register of experience. In addition, we have

learned that the richness of our perceived world is the result of top-down

interpretive and imagistic processes, responsible for fusing together in a coherent

manner the perceptual input. Some of the best evidence in this direction comes

from the analysis of perceptual illusions. Illusions are the result of stimuli that

operate “at the extremes of what our [perceptual] systems have evolved to

handle.”21

This idea that perceptual illusions are indicative of limits within our

sensory systems, despite our still incomplete knowledge of their underlying

mechanisms, is relatively new. Proposals by Herman and Mach in the nineteenth

century that illusions could have a neural basis traceable to lateral interactions

between cells in the visual cortex have been confirmed by recent research. It is

now commonly understood that beyond the retina, connectivity between

neighbouring neurons results in a complex pattern of excitation and inhibition,

which results in enhancing contrast between various regions in the visual field. It

seems thus that the visual system has evolved to respond to change rather than

constancy and while this is a beneficial adaptive function, in some peculiar

instances leads to illusory percepts.22

The lesson from research in perceptual illusions, is that perception is not a

passive relaying of input from the natural environment to the mind/brain but an

active process of selection and construction that serves a specific pragmatic function: survival in the natural world. Perception is active in the sense that the

senses give us an image of the world that is largely the result of adaptive

evolutionary changes hardwired in their dynamic structure. The world of sensory

experience is not the same as that described by physics but only a resultant

projection by the mind/brain based on selective processing of sensory input.

Thus the rich texture of our experience reveals not only our creative/synthesizing

capacities but also our ability to overwrite or at least withstand conditioning

factors in our environment. In addition, psychophysical studies seem to indicate

that it is mainly our ordinary perception, which makes the world appear

seamless. It also shows that perceptual objects as they appear are not entirely

independent of the functioning of our sensory systems. Perceptual illusions

appear as conflicting interpretations that fail to reconcile our assumptions about

the world, as it should normally be, to new psychophysical circumstances.

The co-dependence of various cognitive functions and their action oriented

embeddedness in the natural and social environments reflect a view of human

agency that is very much in tune with the notion of karma. Operating on the

assumption that human beings are inherently good, the Buddhist tradition is less

concerned with how the social and biological forces condition and constrain

human behavior and more with how, given this conditioning, it is possible to

attain freedom. On such a view it is precisely the pattern of co-dependent arising

of phenomena, including subjective states of consciousness, that holds the

promise for release. Knowledge of the pattern of causation at work in the

phenomenal world is of course not sufficient for an individual to follow a course of

action that will be morally beneficial. Disciplined practice is necessary to reverse

human habituation, where such habituation is not conducive to positive human

experiences.

Source Journal of Buddhist ethics