The Zen Teaching of Mu

landscape photography by Osamu Murai / portrait photography by Tadayuki Naito

text by editorial staff

When discussing Zen Buddhism, one often encounters the character for emptiness, mu, in expressions such as “no self,” “no ego,” “no holiness,” and “no permanence.” It is through the actual experience of mu — which means transcending affirmation and negation, being and nonbeing — that satori or spiritual awakening occurs and one can finally come to realize the essential spirit of Zen. Gaining some intellectual understanding is merely a first step in knowing about Zen; to enter into and deepen that understanding, one must experience mu for oneself.

Zen Buddhism is now deeply rooted in Japanese culture. But its spiritual history can be traced back to Shakyamuni Buddha’s great awakening in India, the Indian monk Bodhidharma’s transmitting it to China, and its eventual import into Japan. Legend has it that Bodhidharma introduced Zen to China around 1,500 years ago. Japanese emissary monks later traveled to China, mastered Zen, and returned home; at the same time, Chinese monks made the journey to Japan to transmit Zen. It took centuries, however, for these teachings to evolve into distinct Zen sects here in Japan and for Zen spirit to infuse the culture. This began approximately 700 years ago, during the Kamakura and Muromachi periods (the 1300s).

The teaching of mu is a matter of examining the essential question of whom and what we really are, of being pure at heart, and of no longer being confused by what confronts us. In Japan this teaching has given birth to an art and culture of mu. Ink paintings, calligraphy, dry gardens, the Way of Tea, noh drama, and the like all invoke an intuitive, awesome beauty and sheer simplicity. Among monks who have penetrated this Zen spirit, some have created numerous outstanding masterpieces. Even today, this Zen spirit continues to flow through Japan’s artistic culture.

Ancient Zen teaching goes back more than 1,500 years. However, as recently as the 1960s an international Zen boom burst onto the scene with American hippies taking an active part. Now it is common in the Western media to hear of “Zen style.” It’s often made into an adjective to describe something quiet and calming, or to describe a state of emptiness.

Unless one has actually experienced mu, Zen inevitably appears as something beyond our grasp, somehow mysterious yet captivating.

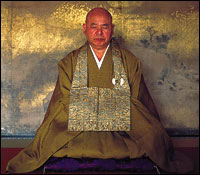

Zen master Keido Fukushima says, “Zen teaches us how to live by inquiring into and clarifying ourselves. This self-questioning is well suited to our contemporary ways of thinking. Rather than seeking salvation through an “other” or through grace, we achieve it on our own. Today, just as in the 1960s, plenty of people profess an interest in Zen. The real difference now is that more of them are willing to go through the practice and find out for themselves.”

In 1969, at the age of 40, Fukushima first traveled to the United States. Since 1989 he has traveled there every year for up to two and a half months at a time, lecturing on Zen at as many as 25 university campuses. His well-received talks, full of humor and wit, are easy to understand.

“The experience of mu may at first glance seem purely negative or passive,” he says, “but it is not so at all. Being mu, or empty of self, allows one to actively take in whatever comes. Our world today and all in it are separated into dualistic distinctions of good and evil, birth and death, gain and loss, self and other, and so on. By being mu, not only does one’s self-centeredness disappear, the conflicts that arise with others dissolve as well. Here is a simple example: When we look at a mountain, we tend to observe it as an object. But if we are mu, we no longer see the mountain as an object; we identify with it; we are the mountain itself. This transcendence of duality may sound like some psychic ability or spiritual power someone possesses. But that is not true. Rather, it is simply and naturally a case of being free, creative, and fresh. We become human beings full of boundless love and compassion.”

Having said this, the fact remains that actually becoming mu is no easy task. This is because it requires eliminating every trace of ego one possesses. It is said that monks training in the monastery can usually remove their conscious delusions in about five years. Removing deep-seated, unconscious delusions, however, requires even more. No matter how interested in Zen one may be, not everyone can devote his life to monastic practice. To Zen master Fukushima, it’s most important for each and every one of us to know about and hold to the goal of “no ego.”

He says, “We are wrapped up in layers of ego including our own individual egos, the egos of our national identities, and so on. To the extent that we let go of ego, the conflicts that surround us can be alleviated. Then a profound sense of loving compassion for others will well up within us. This Zen teaching of being mu is my message to people of the 21st century.”

Zen master Fukushima suggests sitting in zazen (Zen meditation) in the morning and evening for 5 minutes or even 3 minutes or however much time one can afford and in whatever posture we can manage.

“Begin zazen with the intent to look into yourself,” he says. “Then work on emptying yourself. Eventually it will become so much a part of your life that you will feel the day just doesn’t start on the right foot without zazen.”

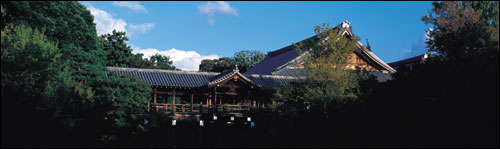

At Tofuku-ji the Tsutenkyo bridge between the Dharma hall and the Buddha hall overlooks the vibrant autumn foliage in the valley below. This is an outstanding example of a Zen monastery compound.

It is not simply freedom from duality, but freedom to respond to it.

Source int.kateigaho.com